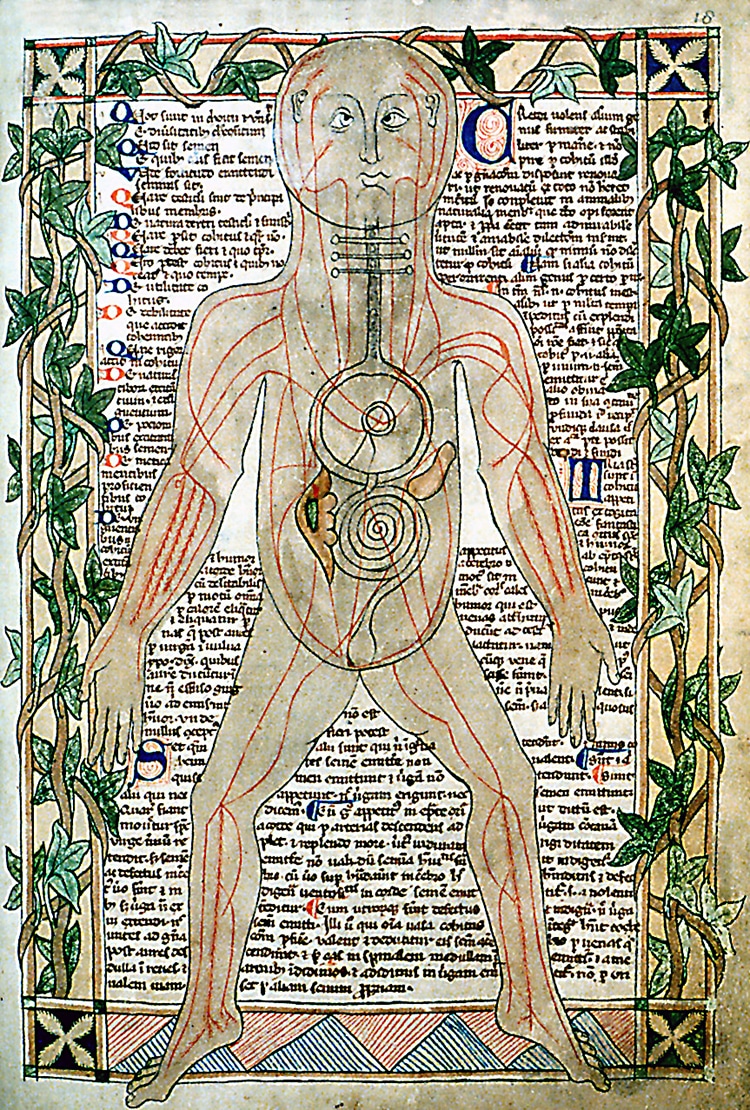

A 13th-century diagram of veins. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Think of medieval doctors and you probably picture a man dressed in robes, perhaps with a plague mask. In the popular imagination, medicine of the Middle Ages is all leeches, bloodletting, and mystical charms and potions. But to a medieval mind, our modern surgery, pharmaceuticals, and blood tests might look just as divorced from scientific reality.

Modern scholars of the history of medicine are attempting to put the record straight by situating these historic practitioners in a long history of scientific inquiry and deduction. Historian Meg Leja of SUNY Binghamton, who recently penned an article for The Conversation, and Peregrine Horden, whose research was recently published in Social History of Medicine, are trying to shift the needle.

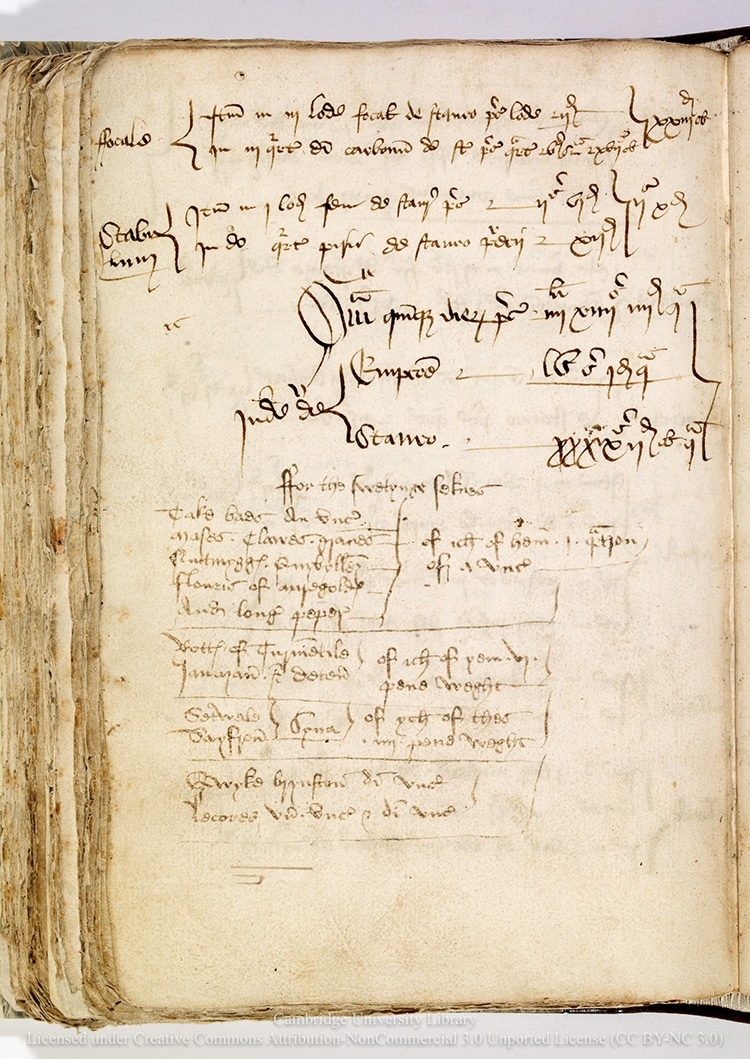

As commented on by Leja, Horden’s article situates bizarre medieval “cures” in contexts that explain the rationale behind the (usually gross) regime. These nasty cures could use the fluids and organs of animals, while others involved mixing herbal ingredients like garlic and mugwort. Historic practitioners were undoubtedly successful in curing ailments—treating infections with antibacterial poultices made with honey or concerns for fresh air allude to modern cures. Unfortunately, without modern developments in childbirth, pharmacology, or surgery, saving patients was certainly harder. The regular reoccurrence of deadly pandemics such as plague also devastated patients.

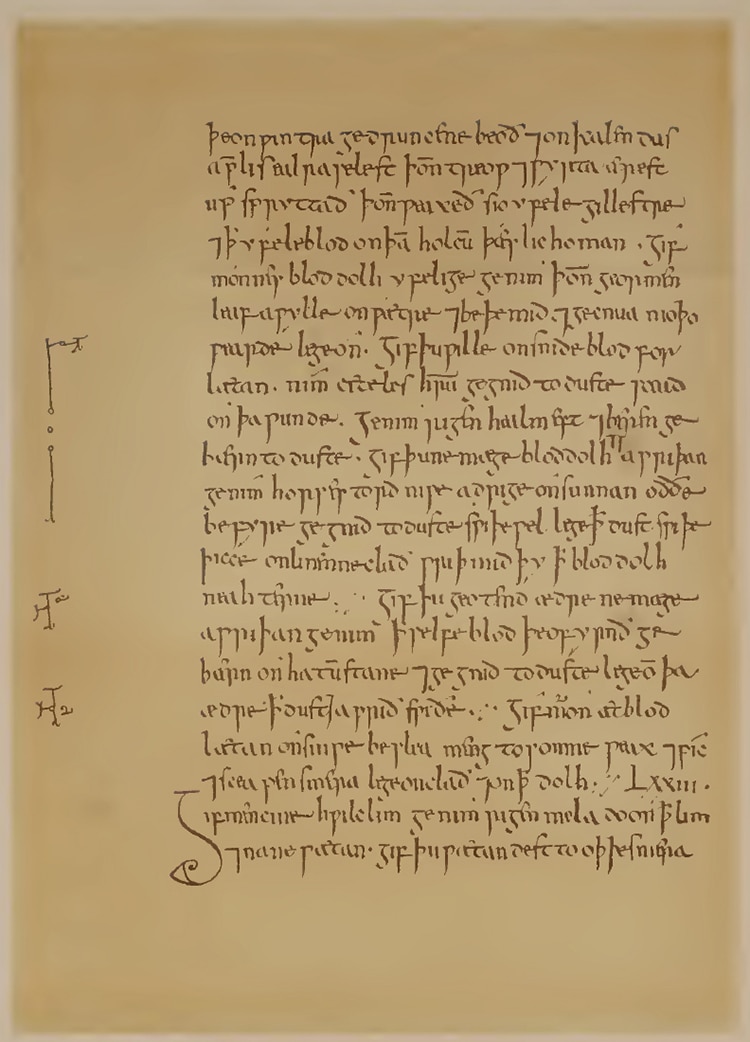

These medieval doctors received inherited medical knowledge from the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians. Yet in the early Middle Ages, often called the Dark Ages, books were rare, and universities just began to form after the year 1000 CE. Monks carefully guarded and copied the remains of ancient knowledge left in Europe.

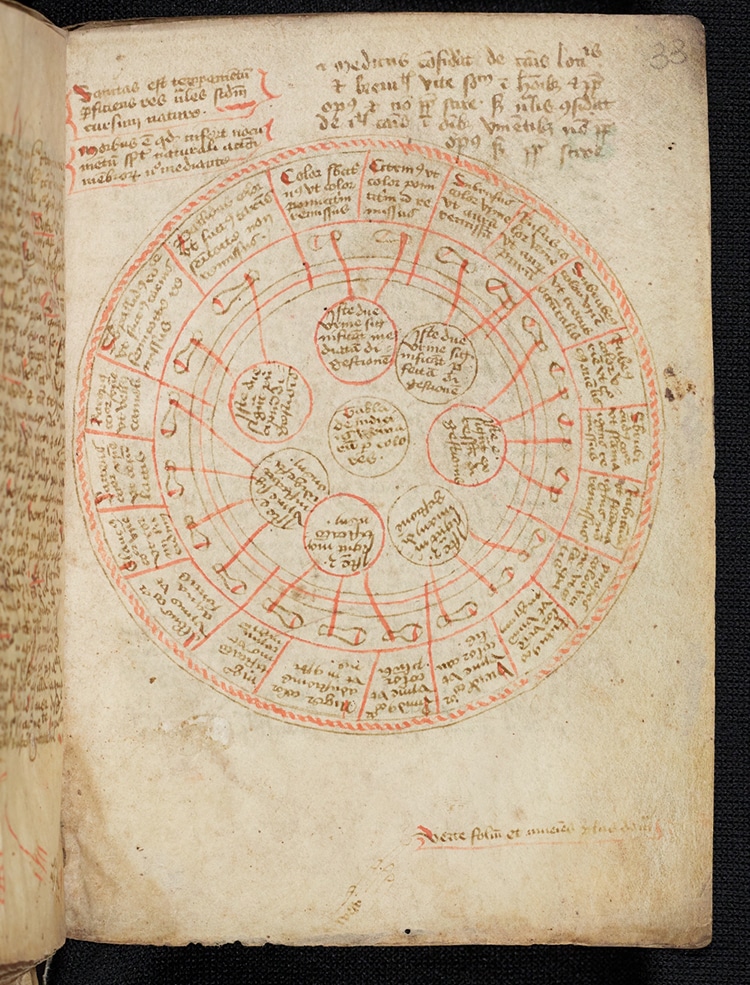

As physicians began to train at universities, they learned to combine this knowledge with practice and rigorous observation. A patient’s fluids and appearance could tell them a lot, just like they inform modern medicine. They then rationally tried to adjust what they observed back to a normal state, perhaps by letting blood to purge toxins or altering a diet to affect the humors of the body.

Early texts from the Dark Ages and into the later medieval period recorded recipes for treatments, signs of disease in urine, and views of veins gained from autopsies. As medieval doctors were far from the only practitioners of healing, their patients would have had a wide variety of treatments to choose from. While today’s patients may prefer a modern X-ray with good reason, there’s less reason to look down our noses at the medieval “quacks.”

One may think of the Dark Ages as a time of quack doctors and magical cures, but medieval medicine was not as divorced from science as we might think.

A 14th-century chart to interpret urine colors. (Photo: Trinity College, Cambridge, CC BY-NC 4.0 DEED)

A 14th-century dentist extracting teeth. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

A 19th-century facsimile of the 10th-century Bald’s Leechbook. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

A selection pf household remedies combined into a book in the 15th century. (Photo: Cambridge University Library/Scriptorium: Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts Online, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED)

h/t: [Smithsonian Magazine, Cambridge University]

Related Articles:

Dutch Metal Detectorist Discovers a Medieval Hoard of Gold Jewelry and Silver Coins

Explore the Impressively Accurate Medieval World Map by a 12th-Century Islamic Scholar

Medieval Masterpiece Found in Elderly Woman’s Kitchen Is Now Headed to the Louvre

Explore the World Through Medieval Eyes on a Map Called the ‘Hereford Mappa Mundi’