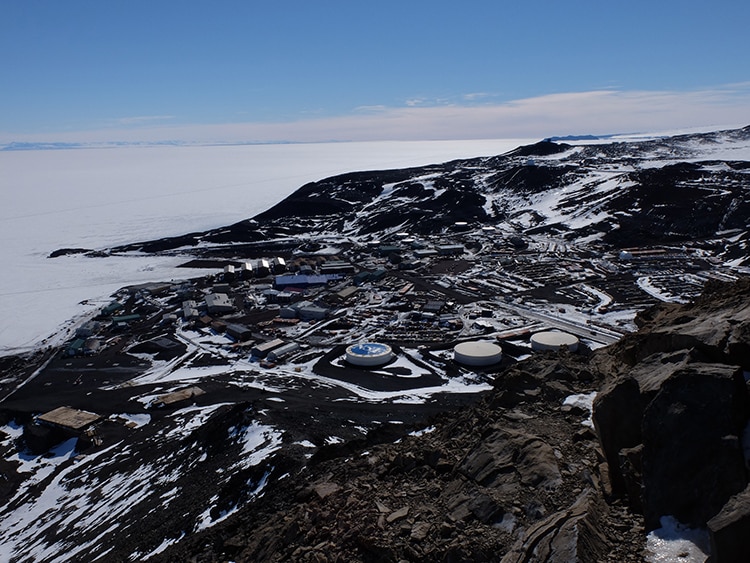

The McMurdo Station, 2014. (Photo: Marco Feldmann/FH Aachen via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0 DEED)

Antarctica is a beautiful yet foreboding place. The only continent without permanent human populations, it boasts a number of scattered research stations which look more akin to Star Wars bases than real homes. For the researchers and support staff who spend months on the continent, the time can be both memorable and difficult, so far from friends and family with limited contact capabilities. Certainly, one gets to know one’s coworkers very well. They also can serve as a fascinating research pool themselves, cut off from the world in almost laboratory conditions. A group of phonetics scholars at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University of Munich used this to their advantage to study the ways accents form and develop. They predicted—and confirmed with data—that a team of isolated scientists actually began to develop a uniquely Antarctic accent.

The phonetics scholars had a selection of the Antarctica-bound individuals record their voices before they left on their mission. Once at Rothera Research Station on Adelaide Island, which is run by the British Antarctic Survey, the study subjects went about their actual own scientific pursuits. For 26 weeks, they endured endless darkness and freezing cold temperatures. They bonded and relaxed with their fellows, who came from a variety of countries but used English to communicate. Slang was often used that would only be intelligible to their fellows, such as “dingle day” for a sunny, blue-sky day or “gonk” meaning to sleep.

Yet while working and playing, they would record themselves weekly saying lists of vowel words. These recordings were eventually provided to the Munich team who analyzed the results. “We wanted to replicate, as closely as we could, what happened when the Mayflower went to North America and the people on board were isolated for a length of time,” Jonathan Harrington, professor at Ludwig-Maximillians-University of Munich, told the BBC. “Six months isn’t very long, so we saw very, very small changes. But we found some of the vowels had shifted.” This accent drift was largely not perceptible to the Antarctic-based speakers, but the computers could detect it. Listening to others affects our pronunciation, and explains how larger shifts can take place with time.

For some of the non-native English speakers, there was a shift in their pronunciation. The study, eventually published in The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, described a German woman’s English shifting to a more “native speaker” accent. This study gives an exceptional amount of insight into the ever-evolving world of language, which is affected by cultural shifts and immigration. For example, since the 1980s, researchers have noted the evolution of Multicultural London English, which evolved after significant Jamaican immigration to London and is visible in cultural developments such as music. Language’s organic nature is fascinating, and from Antarctica to London, there is an endless opportunity to study words, syntax, and the way we relate to one another.

Researchers tracked the way a group of international scientists altered their own pronunciation of words after a winter isolated in Antarctica.

Rothera Research Station. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED)

h/t: [BBC]

Related Articles:

Cristina Mittermeier on the Environmental Trials and Tribulations of Antarctica [Interview]

Interview: Photos of Adorable Penguins in Antarctica Raise Awareness of Their Changing Habitat

This Is What Antarctica Looks Like Beneath the Ice

Iceberg the Size of London Breaks off Antarctica’s Brunt Ice Shelf