Moved by a desire to be among people who live their lives in close contact with nature, photographer Drew Doggett traveled to South Sudan. He made the voyage specifically to photograph the Mundari people, a small tribe whose culture is centered around their livestock. During his time in the country, he camped with the Mundari and was able to document their traditions.

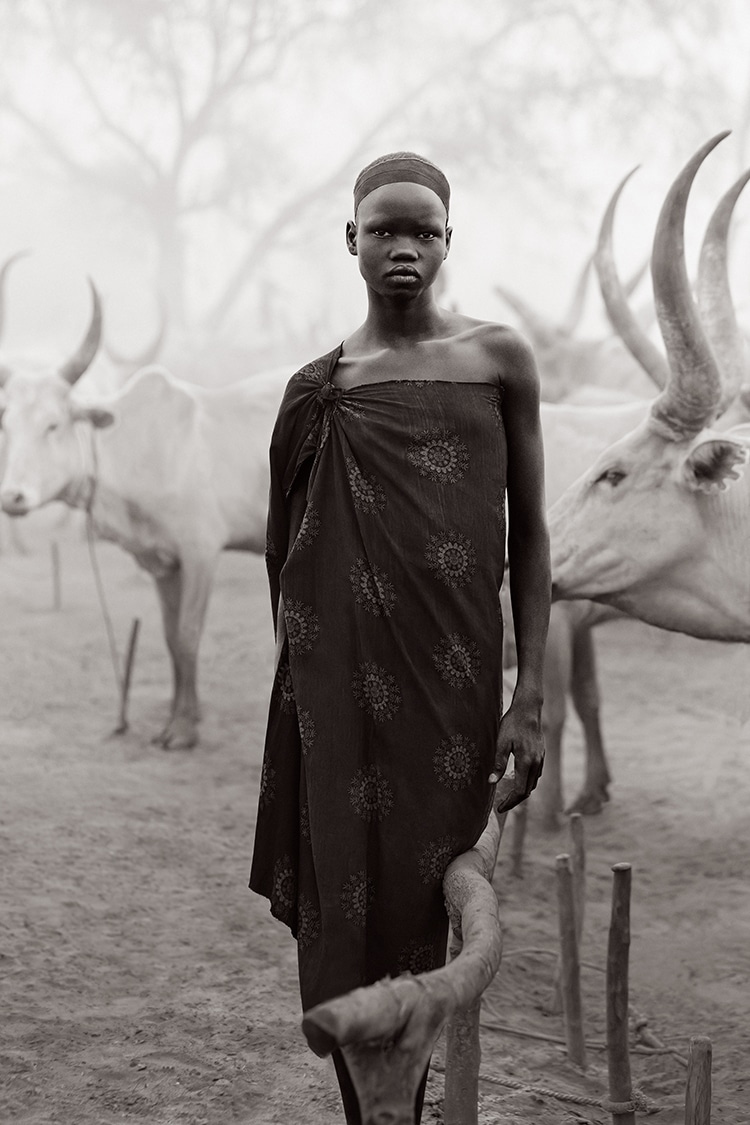

With a background in the fashion industry, Doggett brings a unique sensibility to this type of photography. The resulting series, Spirit of the Earth, is a powerful look at the Mundari that documents the scene while also elevating it to fine art. In many images, we see the dust kicked up by the cattle form a misty haze, creating an air of mystery. Doggett invites us, as viewers, to observe the scenes and find the small details that give clues to the lives of these people.

At the same time, he also presents powerful portraits where humans and animals are on a level playing field. This mirrors the way that the Mundari themselves feel about their livestock, which is used as currency and as a symbol of status.

We had a chance to speak with Doggett about the series and what drew him to the story of the Mundari. We also chatted about what type of planning goes into traveling to South Sudan and the photographer’s sense of responsibility when shooting this type of cultural imagery. Read on for My Modern Met’s exclusive interview.

How did the Mundari tribe first land on your radar, and what was it that attracted you to their story?

I’ve always been fascinated by cultures, especially those that are in touch with the natural world around them. Like so many others who have found inspiration in the Indigenous communities of Africa, Sebastião Salgado’s work in the region furthered my interest in the communities of Sudan. I vividly remember seeing images of the pastoral, nomadic people in Sudan (now South Sudan) in their cattle camps with their prized longhorn cattle, covered in ash and confidently gazing back at the camera. At the time—around 2006—I was working in fashion, but these images stayed with me, and when I began my independent practice as an artist, I revisited traveling there every year.

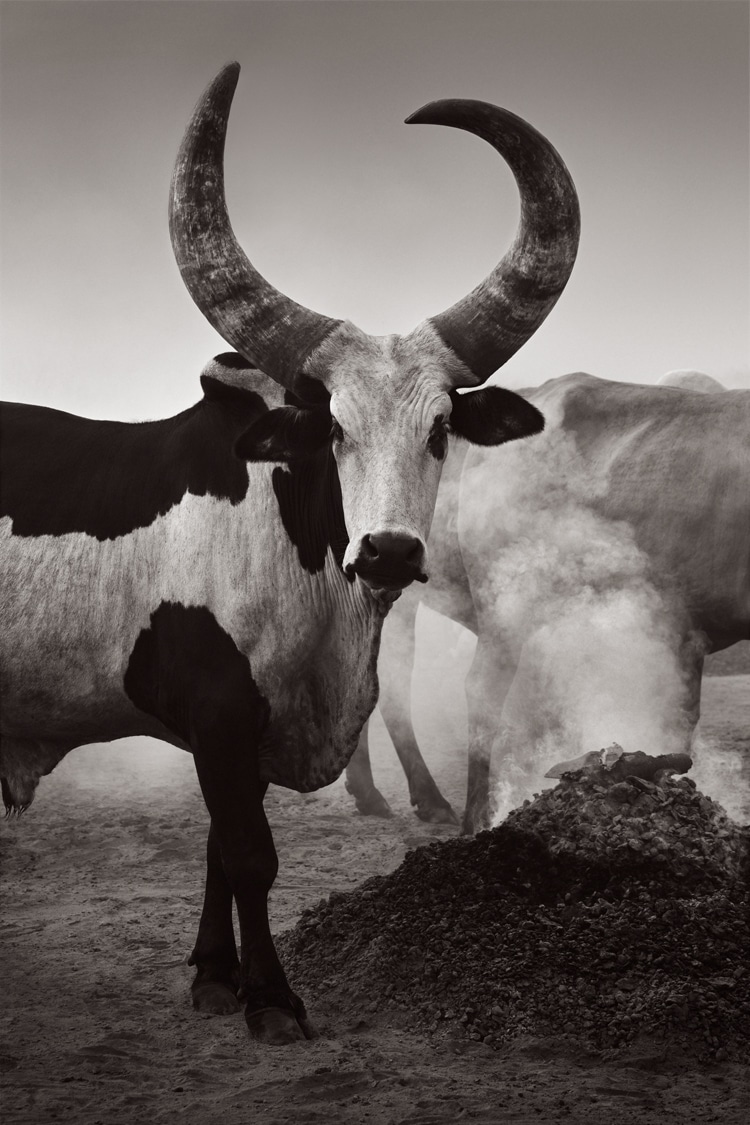

These cattle camps were etched in my mind; the drama and scale captivated me, and I loved the bond the people shared with their animals. Not to mention their cattle are a unique breed, the Ankole-Watusi, who have these incredible, sculptural horns that lend them majesty.

It was dangerous to travel to South Sudan for a long time, but I began to keep my eye on opportunities and bookmarked a number of cultures that I would love to spend time among. The Mundari tribe was one of them, as they are a peaceful people whose lives revolve around the welfare of their cattle and keeping the rhythms of their existence in line with those of Mother Earth. To me, this made the Mundari’s world a visual story worth telling.

What sort of research and planning went into executing this story?

I had been planning the execution of this story for years, reading about the pastoral communities in this area and, in my mind, crafting the images I wanted to take. A large part of this process was also exploring the options of how I could reach these communities. Regardless, my primary focus is always figuring out how and why my images will do justice to the story, as I find cultural portraits like these to come with an immense responsibility to the subject.

How much time did you spend with the Mundari, and how were you able to connect with them?

Due to the fraught nature of this region, your time in South Sudan as a visitor—especially somewhere remote like where the Mundari were along the Nile—is limited. For this series, I relied on the expertise of another photographer, Trevor Cole, who has been to this region many times. Beyond his experience, hiring a local guide who can help you connect and communicate with people is key. I also always aim to find a guide who knows the culture well.

To create this series, I spent several days camping alongside the Mundari, waking up before dawn to wander the camps with them. The mornings are so calm and peaceful, and man and animal could often be found warming themselves around the same campfire. The Mundari are very proud of their cattle, and many of them had a favorite cow they wanted to share with me.

What was the most challenging part of shooting the series?

The most challenging part of shooting a series like this is, without a doubt, how overwhelming it can be to the senses and how hard of a challenge it is to capture everything you want viewers to digest. The scale of this camp is almost impossible to imagine, so figuring out how to photographically compose the scene is quite the task. My days soon became about whether I wanted to create an image that draws the viewer into a single subject within the frame, or if I wanted people to scan the scene before them to unearth interesting elements. Among this chaos, I still wanted to maintain a level of uniformity so observers could lose themselves in the scene as they scan the image, and to keep a certain level of artfulness in the final works.

Another challenging element was the window of time I had to create the work. The sun is extremely harsh, and it rises and sets quickly. So, the dramatic scenes I wanted to capture, created by light streaming through the smoke, are visible only for a very short time before the setting or rising sun renders everything too harsh or it’s just too dark.

What do you think that people would be most surprised to learn about the Mundari?

The most surprising part of life in the Mundari cattle camps is how everything moves like clockwork, and twice a day, these camps would go from organized chaos ablaze with life to total ghost towns. It was simply incredible. Each morning the camps would empty out as the cattle set out to graze or drink nearby, but by evening, it was a whole different story. Thousands of cattle descended on the camp, and the air would swell with dust, and music played on horns with the cattle returning to their owners by way of the songs they recognized. The men would stay up, often quite late, playing music and socializing, and by morning the camps would be exceptionally quiet once again.

What are you hoping to transmit to the public with this work?

The dramatic scenes of humanity I found among the Mundari were unlike anything I had ever experienced. Their ability to live within the Earth’s cadence was a reminder of how much we can all gain from listening to our planet’s rhythms and working together. Through these images, I wanted to share the incredible scenes of life in their camps with man and animal peacefully coexisting. These people have so much respect for their cattle, and their sense of community and pride in their way of life is something I wanted to convey through my images.

As I mentioned, there’s a lot of responsibility in photographing a subject like this. My goal for these images was for viewers to walk away with a profound appreciation for a way of life that is, most likely, completely foreign to their own. For me, taking photographs like this is a way of preserving our world on camera and revealing shared humanity, especially as, for better or for worse, people get pulled away from these traditional ways of life. I also want people to engage with my images in an exploratory way. My hope is that each time you look at one of these works, you find something new and exciting to marvel at.

Another aspect of the responsibility of taking cultural portraits is that there is always a risk that, once again, it may be hard to travel there. In fact, a few weeks after I returned, the neighboring country of Sudan erupted in fighting, which may impact visitors to South Sudan. I feel pretty lucky about the timing of my trip there.