Although he died over 450 years ago, Michelangelo remains one of the most famous artists of all time. As one of the masters of the Italian Renaissance, his paintings and sculptures are still used today as examples of this fruitful time in history. While his frescoes in the Sistine Chapel are certainly a large part of his legacy, Michelangelo always considered himself a sculptor rather than a painter. Over a long and rich career that spanned nearly seven decades, he produced stunning marble sculptures that have inspired artists for centuries.

From his very early days in Rome to a blossoming career in Florence, Michelangelo was able to produce sculptures that defied expectations. His manipulation of the medium allowed him to carve out realistic anatomy, as well as flowing hair and clothing. Whether working on mythological figures or a religious subject, he made unique creative choices that proved his genius.

Let’s take a look at some of Michelangelo’s most important sculptures, from his iconic David to the intimate, personal work made in the last years of his life.

Explore 8 famous sculptures by Renaissance artist Michelangelo.

David

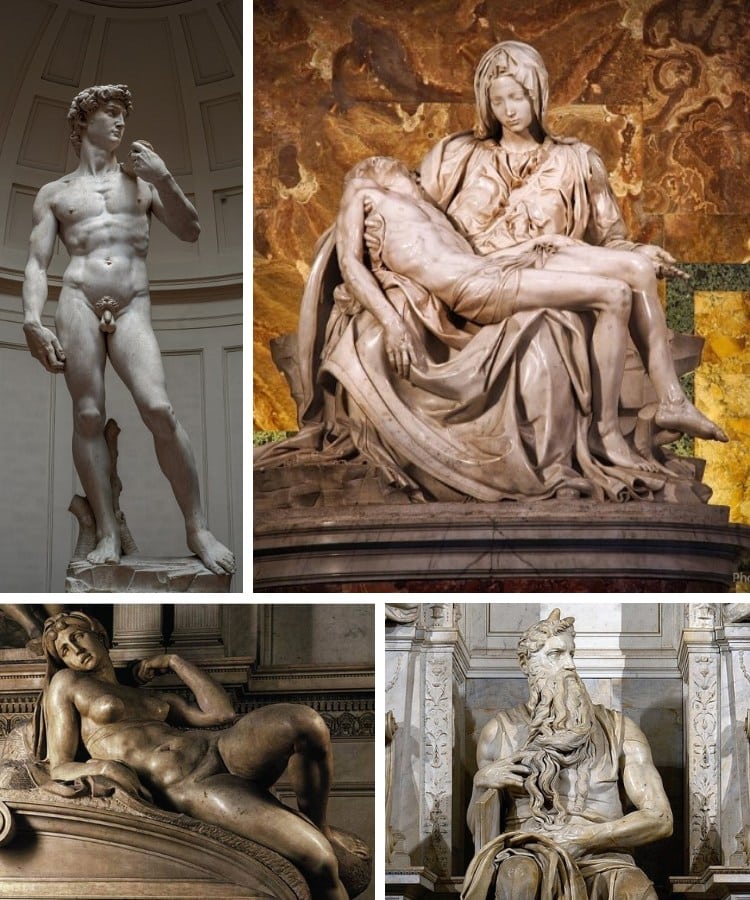

Photo: Michelangelo via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

|

Title

|

David

|

|

Artist

|

Michelangelo

|

|

Year

|

c. 1501–1504

|

|

Medium

|

Marble

|

|

Size

|

517 cm × 199 cm (17 ft × 6.5 ft)

|

|

Location

|

Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy

|

When thinking about Michelangelo’s art, his sculpture David is probably the first one that comes to mind. The sculptor was only 26 when he was commissioned to make a statue that would sit along the roof of Florence’s main cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore. Once completed, it was clear that the 17-foot-tall marble sculpture was too big to lift, so it stayed firmly on the ground. A replica of the original still stands in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria, while the original is located in the city’s Accademia Gallery.

The sculpture depicts David from the Biblical story of David and Goliath. In Michelangelo’s version, David is cool, calm, and collected. He gazes off to the side with his slingshot over his shoulder and hip jutted out to give his body contrapposto. Michelangelo’s David became instantly famous for its extremely lifelike anatomy and the way in which he portrayed David as a young man ready to go into battle. This was different from previous versions, which typically showed David after he slayed Goliath. One of the exemplary sculptures of the Italian Renaissance, it’s often used as an example of the period’s creative genius. In 2023, David hit the international news when a principal in Florida was forced to resign when parents complained after an image of the sculpture was shown in the classroom.

Bacchus

Photo: Michelangelo via Wikimedia Commons (Public domain)

|

Title

|

Bacchus

|

|

Artist

|

Michelangelo

|

|

Year

|

1496–1497

|

|

Medium

|

Marble

|

|

Size

|

203 cm (80 in)

|

|

Location

|

Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy

|

When Michelangelo was 21 years old, he moved to Rome at the invitation of a powerful patron—Cardinal Raffaele Riario. And it was Riario who commissioned this sculpture, Bacchus, from the young artist. The sculpture is an oversized depiction of the Roman god of wine, a subject most likely suggested by Riario, who was an antique collector.

The sculpture shows off Michelangelo’s ability to work with marble and create art that competed with—and even surpassed—Hellenistic sculpture. The difference here is that Bacchus is depicted enjoying his wine a bit too much and raises his glass while leaning back in a drunken, almost suggestive manner. Ultimately, Riario rejected the sculpture for these reasons as he felt the sculpture was oversexualized. Luckily, it was eventually purchased by the cardinal’s banker for his garden and somehow made its way to Florence, where it can still be found at the Bargello Museum.

La Pietà

Photo: Toby Jorgensen via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0)

|

Title

|

La Pietà

|

|

Artist

|

Michelangelo

|

|

Year

|

1498–1499

|

|

Medium

|

Marble

|

|

Size

|

174 cm × 195 cm (68.5 in × 76.8 in)

|

|

Location

|

Saint Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City, Italy

|

A striking contrast to Bacchus is Michelangelo’s La Pietà, which is the only other sculpture existing from this early period when the artist lived in Rome. It was commissioned in 1497, just a year after he moved to the city, by the French ambassador to the Holy See.

Though not a Biblical story, the theme is commonly found in Christian art and shows the Virgin Mary cradling Jesus in her lap after the Crucifixion. Michelangelo’s version was carved from a single block of Carrara marble and was revolutionary due to the artist’s creative choices. He chose to depict Mary as a beautiful young woman rather than portray the actual age difference between mother and son. Michelangelo also used a triangular composition. While this causes the figures to be out of proportion, it ultimately creates visual harmony and balance.

The sculpture was immediately a success, and Michelangelo was so proud of it that it was the only sculpture he ever signed. The work is in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, where it sits behind plexiglass. The protective barrier was put in place after a man with mental health issues attacked the sculpture in 1972, damaging several parts of the Virgin Mary.

Slaves or Prisoners

(Left) Rebellious Slave. (Photo: Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0) / (Right) Dying Slave. (Photo: Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

|

Title

|

Slaves or Prisoners

|

|

Artist

|

Michelangelo

|

|

Year

|

1513 – 1516, 1520 – 1523, 1530 – 1534

|

|

Medium

|

Marble

|

|

Size

|

varies

|

|

Location

|

Louvre, Paris, France and Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy

|

Collectively known as Slaves or Prisoners, this series of unfinished sculptures was created for the Tomb of Julius II. Though Michelangelo worked on the tomb for 40 years, it was delayed while he worked on the Sistine Chapel ceiling and ultimately never fully realized. The six sculptures are in various stages of completion, with the Dying Slave and Rebellious Slave—which are now housed in the Louvre—being the most finished.

All of the figures are masterful in their depiction of anatomy and have dynamic poses. Many of them are struggling to free themselves, and some of the most unfinished sculptures look to be rising from the marble. Though Michelangelo’s original vision of the tomb, which contained 40 figures, was never realized, these incredible sculptures offer a look at his creative genius.

Moses

Photo: Livioandronico2013 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

|

Title

|

Moses

|

|

Artist

|

Michelangelo

|

|

Year

|

c. 1513–1515

|

|

Medium

|

Marble

|

|

Size

|

235 cm × 210 cm (92.5 in × 82.6 in)

|

|

Location

|

San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome, Italy

|

Also created for the Tomb of Julius II, this sculpture was created around 1513 to 1515—the same time as the Slaves. As opposed to those statues, Moses was completed and sits as the central figure of Pope Julius II’s tomb. Though the final design was greatly reduced, the tomb, which is located in Rome at San Pietro in Vincoli, is still a wonderful display of Michelangelo’s talents. Moses is an imposing figure, and certainly not one to be messed with.

Michelangelo depicts him with rippling biceps, and he looks to the side as his fingers caress his long beard. The horns on his head are owed to a translation error in the Latin Bible that was used at the time. The sculpture shows off Michelangelo’s ability to create different textures in marble and create a sense of mystery and narrative in his figures. We aren’t sure where Moses is looking and why he’s stroking his beard, but Michelangelo certainly encourages us to take our best guess.

Sculptures from the Medici Chapel

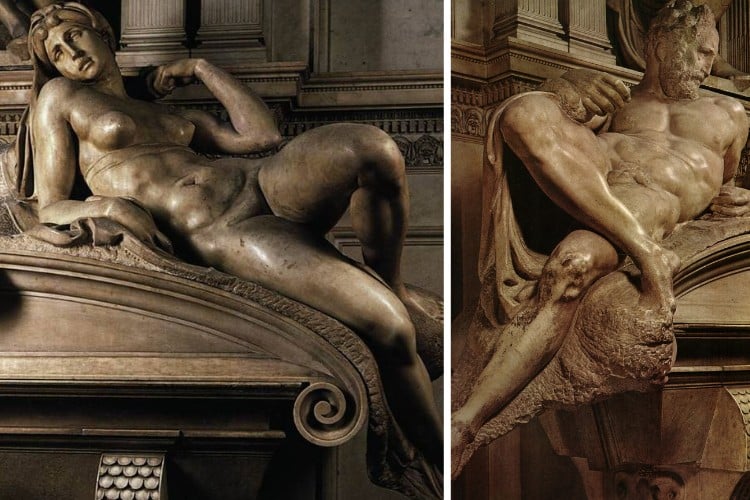

(Left) Dawn. (Photo: eos1 via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0) / (Right) Dusk. (Photo: Michelangelo via Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

|

Title

|

Dawn, Dusk, Night, Day

|

|

Artist

|

Michelangelo

|

|

Year

|

1526–1531 (Day and Night); 1524–1530 (Dawn); 1524–1534 (Dusk)

|

|

Medium

|

Marble

|

|

Size

|

varies

|

|

Location

|

New Sacristy, Medici Chapel, San Lorenzo Basilica, Florence, Italy

|

The Medici family was the great banking family that ruled Florence during the Renaissance. Members of the family were great patrons of Michelangelo, and he was charged with designing the chapel that acted as a mausoleum for several of them. The New Sacristy is located in Florence’s Basilica of San Lorenzo. Michelangelo first worked on the project as an architect and then created the sculptural details on the tombs of Lorenzo de’ Medici and Giuliano de’ Medici.

Sculptures that symbolize Dusk and Dawn sit on Lorenzo’s tomb, while other sculptures that are metaphors for Night and Day adorn Giuliano’s tomb. Michelangelo worked on all of the sculptures from around 1524 until about 1534. He drew on ancient sculpture to create the posts for the oversized sculptures of men and women. Rippling and muscular, they appear strikingly similar to some of the painted figures in the Sistine Chapel. Interestingly, Dawn and Night are the only female nudes he ever made. The sculptures have been extremely popular since their creation, with copies and casts found in different museums around the world.

The Deposition

Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY 2.5)

|

Title

|

The Deposition

|

|

Artist

|

Michelangelo

|

|

Year

|

c. 1547–1555

|

|

Medium

|

Marble

|

|

Size

|

277 cm (109 in)

|

|

Location

|

Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence, Italy

|

Sometimes called the Bandini Pietà, The Deposition is a powerful sculpture created toward the latter half of Michelangelo’s career. Completed in 1555, it shows Christ being taken down from the cross by Nicodemus, the Virgin Mary, and Mary Magdalene. According to Giorgio Vasari, a late Renaissance artist and historian, Michelangelo created the sculpture for his own tomb but later intentionally damaged it and gifted it to one of his servants.

Michelangelo was well into his 70s when he began the sculpture. Vasari wrote that he started the piece to keep his mind active in his later years. It must have been a deeply personal piece. In fact, it’s widely accepted that he included a self-portrait on the face of Nicodemus. There are many theories behind why he would have damaged his own sculpture after eight years of work. Some say that he was frustrated by a vein in the marble that was giving him trouble, while others feel it might have been a way to hide a belief known as Nicodemism. Nicodemists agreed with Protestants, except they wished to stay with the Catholic church instead of breaking away. By putting his features on the face of Nicodemus, Michelangelo may have been fearful that his beliefs would be discovered by the wrong people and decided to break the sculpture as a way to get it out of his studio.

Luckily for us, the servant who received Michelangelo’s gift sold it to a man named Francesco Bandini. Bandini had the sculpture restored and it’s now part of the collection at Florence’s Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

Rondanini Pietà

Photo: Paolo da Reggio via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

|

Title

|

Rondanini Pietà

|

|

Artist

|

Michelangelo

|

|

Year

|

1555–1564

|

|

Medium

|

Marble

|

|

Size

|

195 cm (77 in)

|

|

Location

|

Castello Sforzesco, Milan, Italy

|

Michelangelo worked on this version of the pietà for twelve years, last taking a chisel to it six days before he died. Like many of his final sculptures, the Rondanini Pietà is a look at Michelangelo’s mortality and was likely created for his tomb. The elongated figures stand in stark contrast to the robust, muscle-bound figures Michelangelo depicted in his youth. In this version, Mary is standing behind her son and gently takes on the weight of his body.

A sketch Michelangelo created for the sculpture is now in the collection at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. From this sketch, we can see that he improvised greatly with the marble. Originally, Mary’s face was turned to the right, and there are still slight traces of that in the marble. At some point, he decided to turn her face to look down at her son, creating a greater sense of intimacy. Christ’s right arm, which is broken off, is likely left over from the original composition and would have probably been removed before the sculpture was complete.

Related Articles:

A Detailed Look at Bernini’s Most Dramatically Lifelike Marble Sculpture

Who Was Michelangelo? Get to Know the Renaissance Sculptor and Painter

Learn How Donatello’s ‘David’ Statue Paved the Way for Sculptors in the Renaissance

Learn the Intriguing (and Sometimes Controversial) History Behind Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgment’