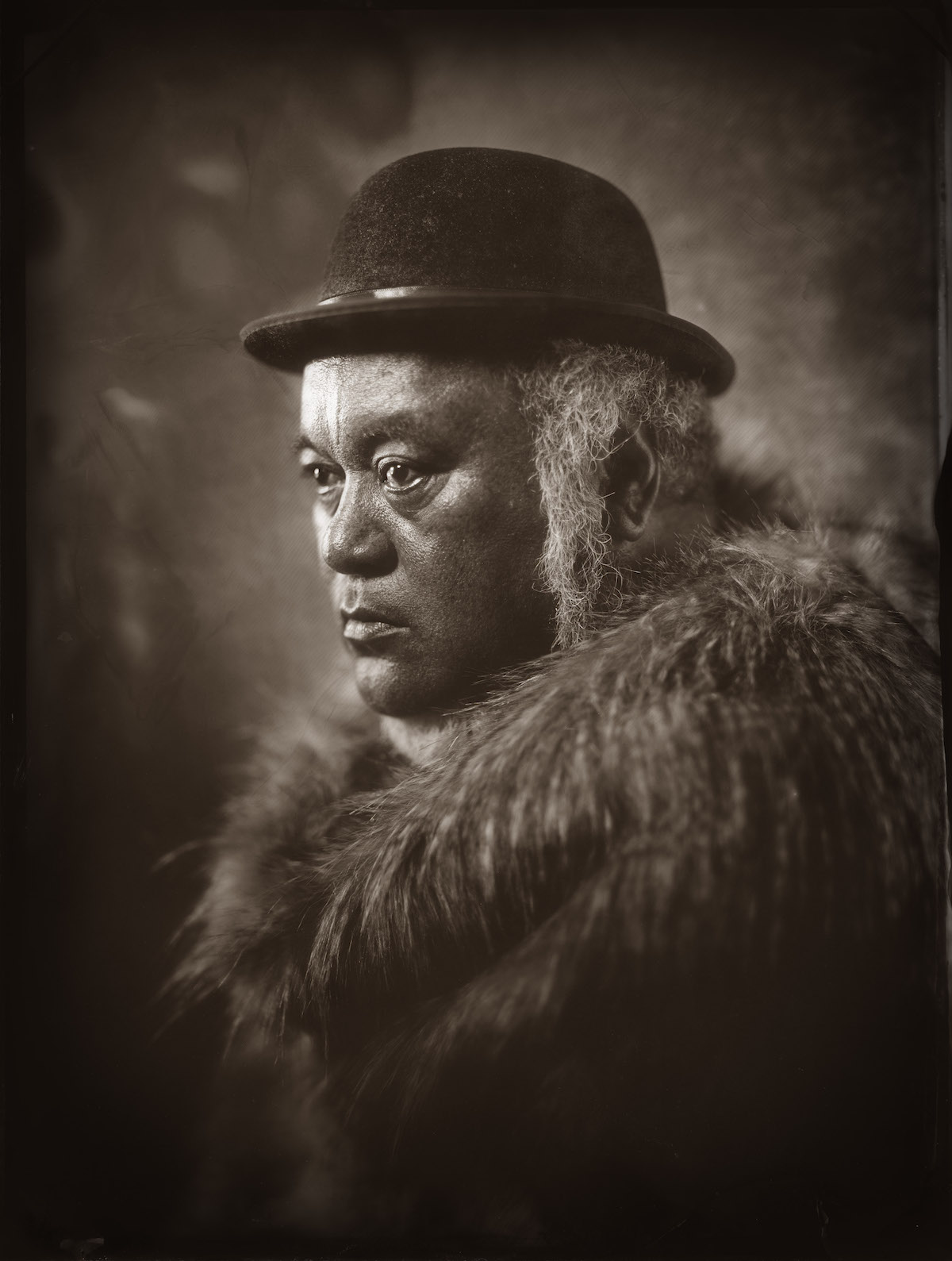

Gary Shane Te Ruki

Inspired by wet plate portrait photography of the past, photojournalist Michael Bradley‘s Puaki is an examination of the Māori culture. Specifically, Bradley explores tā moko, the permanent markings on the face and body practiced by New Zealand’s indigenous culture. With his set of stunning portraits, he visually recalls the near erasure of this important cultural tradition.

Bradley, who has been practicing wet plate photography since 2013, first stumbled upon the concept for Puaki when looking at wet plate images where people’s tattoos often didn’t appear. This was a spark to investigate the history of tā moko and develop the long-term project.

“In Māori culture, it is believed everyone has a tā moko under the skin, just waiting to be revealed,” writes the Te Kōngahu Museum of Waitangi. “The problem is, when photographs of tā moko were originally taken in the 1850s, the tattoos barely showed up at all. The wet-plate photographic method used by European settlers served to erase this cultural marker—and as the years went by, this proved true in real life, too. The ancient art of tā moko was increasingly suppressed as Māori were assimilated into the colonial world.”

Tā moko has seen a resurgence since the 1990s and the pride each participant takes in their markings is clear in Bradley’s photographs. By comparing the digital and wet plate photographs, it’s clear that tā isn’t only about personal expression, but a cultural marker that is worn with dignity.

Puaki, which means “to come forth, show itself, open out, emerge, reveal, to give testimony,” is Bradley’s way to plant a seed with the public. He hopes they will learn more about tā moko and how Māori culture forms an integral part of modern society. Almost erased from the pages of history, the practice is a demonstration of how cultural traditions can continue to flourish in the modern age.

Puaki is on view at the Te Kōngahu Museum of Waitangi in New Zealand until September 2, 2018.

Puaki focuses on the tā moko of the Māori by juxtaposing digital and wet plate portraits.

Paora Rangiaho

Paora Rangiaho

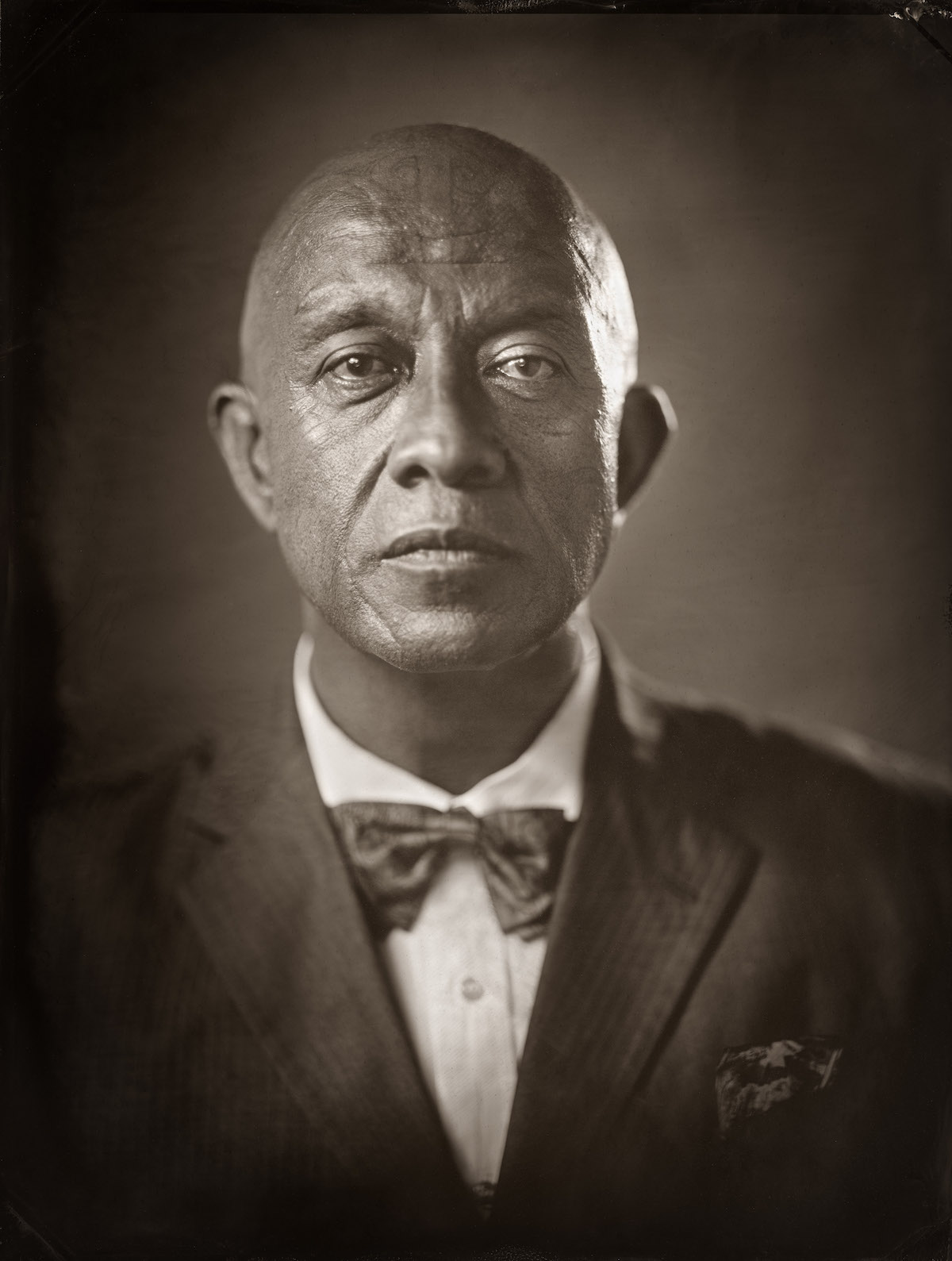

Te Kahautu Maxwell

Te Kahautu Maxwell

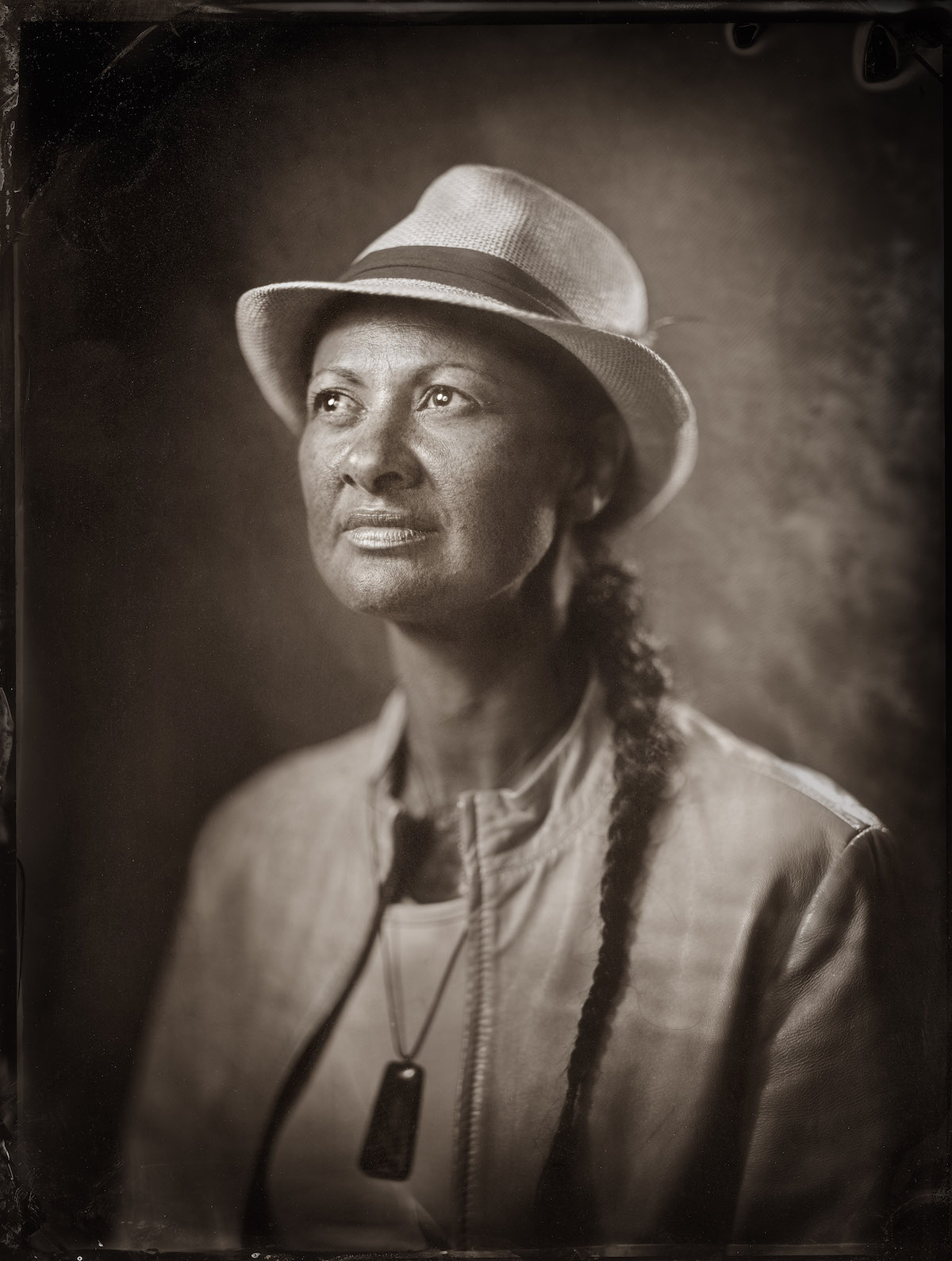

Naomi Tracey Robinson

Naomi Tracey Robinson

The 19th-century technique seems to “erase” the subjects’ facial tattoos, much as tā moko almost disappeared until a resurgence in the 1990s.

Pouroto Nicholas Hamilton Ngaropo

Pouroto Nicholas Hamilton Ngaropo

Catherie Murupaenga-Ikenn

Catherie Murupaenga-Ikenn

Tunuiarangi Rangi McLean

Tunuiarangi Rangi McLean

Whare Isaac-Sharland

Whare Isaac-Sharland

Photojournalist Michael Bradley also interviewed all the participants, with individual films available on the Puaki website.

Michael Bradley: Website | Facebook

My Modern Met granted permission to use photos by Michael Bradley.

Related Articles:

Emotional Haka Wedding Dance Beautifully Displays Maori Tradition of Pride and Respect

Wet-Plate Collodion Technique Applied to Old Tin Cans

Creating a Time Machine with Wet Plate Collodion Prints

Photographer Takes Arresting Tintype Portraits of Random Visitors