“The big buzz” by Karine Aigner (USA). Wildlife Photographer of the Year Overall Winner and Winner, Behavior: Invertebrates.

Karine Aigner gets close to the action as a group of bees compete to mate.

Using a macro lens, Karine captured the flurry of activity as a buzzing ball of cactus bees spun over the hot sand. After a few minutes, the pair at its center—a male clinging to the only female in the scrum—flew away to mate.

The world’s bees are under threat from habitat loss, pesticides, and climate change. With 70% of bee species nesting underground, it is increasingly important that areas of natural soil are left undisturbed.

A cluster of male bees locked in a struggle to see who has what it takes to mate with the lone female gave photographer Karine Aigner the photo she needed to take home the title of Wildlife Photographer of the Year. The American photographer came out victorious to become only the fifth woman in the photo contest’s 58 years to earn the top prize. Run by the UK’s Natural History Museum the prestigious contest attracts the top wildlife photographers from around the world.

“Wings-whirring, incoming males home in on the ball of buzzing bees that is rolling straight into the picture,” shares Rosamund Kidman Cox, chair of the jury. “The sense of movement and intensity is shown at bee-level magnification and transforms what are little cactus bees into big competitors for a single female.”

Aigner, a former National Geographic picture editor, was not only named Wildlife Photographer of the Year, but she also won the Photojournalism Story Award for her look at the tradition of songbirds in Cuban culture. Good storytelling dominated the competition, and wildlife photographers who were able to create a strong narrative were rewarded.

Among the notable category winners is Mexico’s Fernando Constantino Martínez Belmar. He won the Behavior: Amphibians and Reptiles category for his incredible close-up of a Yucatan rat snake with a bat in its mouth. The snake faces directly into the camera with the bat wings hanging symmetrically from its mouth. In an instant, we know the snake will be back in its lair, feasting on its snack. Thanks to Belmar’s quick trigger finger, we get to view the snake’s moment of victory.

The winners were selected after an intense process of narrowing the 38,575 entries down to a shortlist. Now the public will be able to enjoy the winning images in a redesigned flagship exhibit at the Natural History Museum. The photos will be positioned among short videos, quotes from jury members and photographers, as well as insights from museum scientists to invite visitors to explore how human actions continue to shape the natural world.

Here are the winning photos from the Natural History Museum’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year contest.

“The bat-snatcher” by Fernando Constantino Martínez Belmar (Mexico). Winner, Behavior: Amphibians and Reptiles.

Fernando Constantino Martínez Belmar waits in darkness as a Yucatan rat snake snaps up a bat.

Using a red light to which both bats and snakes are less sensitive, Fernando kept an eye on this Yucatan rat snake poking out of a crack. He had just seconds to get the shot as the rat snake retreated into its crevice with its bat prey.

Every evening at sundown in the Cave of the Hanging Snakes, thousands of bats leave for the night’s feeding. It is also when hungry rat snakes emerge, dangling from the roof to snatch their prey in mid-air.

The beauty of baleen by Katanyou Wuttichaitanakorn (Thailand). Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year Overall Winner and Winner 15-17 Years.

Katanyou Wuttichaitanakorn is intrigued by the contrasting colors and textures of a Bryde’s whale, which surfaces close by.

Following government tourism guidelines, the tour boat Katanyou was traveling on turned off its engine as the whale appeared close by. This meant that Katanyou had to steady his hands to capture this close-up composition as the boat rocked in the swell.

Bryde’s whales have up to 370 pairs of gray-colored plates of baleen growing inside their upper jaws. The plates are made of keratin, a protein that also forms human hair and nails, and are used to filter small prey from the ocean.

“The dying lake” by Daniel Núñez (Guatemala). Winner, Wetlands – The Bigger Picture.

Daniel Núñez uses a drone to capture the contrast between the forest and the algal growth on Lake Amatitlán.

Daniel took this photograph to raise awareness of the impact of contamination on Lake Amatitlán, which takes in around 75,000 tonnes of waste from Guatemala City every year. ‘It was a sunny day with perfect conditions,’ he says, ‘but it is a sad and shocking moment.’

Cyanobacteria flourishes in the presence of pollutants such as sewage and agricultural fertilizers forming algal blooms. Efforts to restore the Amatitlán wetland are underway but have been hampered by a lack of funding and allegations of political corruption.

“Spectacled bear’s slim outlook” by Daniel Mideros (Ecuador). Winner, Animals in their Environment.

Daniel Mideros takes a poignant portrait of a disappearing habitat and its inhabitant.

Daniel set up camera traps along a wildlife corridor used to reach high-altitude plateaus. He positioned the cameras to show the disappearing natural landscape with the bear framed at the heart of the image.

These bears, found from western Venezuela to Bolivia, have suffered massive declines as the result of habitat fragmentation and loss. Around the world, as humans continue to build and farm, space for wildlife is increasingly squeezed out.

“The great cliff chase” by Anand Nambiar (India). Winner, Behavior: Mammals.

Anand Nambiar captures an unusual perspective of a snow leopard charging a herd of Himalayan ibex towards a steep edge.

From a vantage point across the ravine, Anand watched the snow leopard maneuver uphill from the herd. It was perfectly suited for the environment—unlike Anand, who followed a fitness regime in preparation for the high altitude and cold temperatures.

Snow leopards live in some of the most extreme habitats in the world. They are now classed as vulnerable. Threats include climate change, mining, and hunting of both the snow leopards and their prey.

Nearly 40,000 photographs were entered into the 58th edition of the prestigious photo contest.

“Under Antarctic Ice” by Laurent Ballesta (France). Winner, Portfolio Award.

Living towers of marine invertebrates punctuate the seabed off Adelie Land, 32 meters (105 feet) under East Antarctic ice. Here, at the center, a tree-shaped sponge is draped with life, from giant ribbon worms to sea stars.

Laurent Ballesta endures below-freezing dives to reveal the diversity of life beneath Antarctica’s ice.

An underwater photographer and biologist, Laurent has led a series of major expeditions, all involving scientific mysteries and diving challenges, and all resulting in unprecedented images. He has won multiple prizes in Wildlife Photographer of the Year, including the grand title award in 2021.

His expedition to Antarctica, exploring its vast underwater biodiversity, took two years to plan, a team of expert divers, and specially developed kit. His 32 dives in water temperature down to -1.7˚C (29°F) included the deepest, longest dive ever made in Antarctica.

“New life for the tohorā” by Richard Robinson (New Zealand). Winner, Oceans: The Bigger Picture.

Richard Robinson captures a hopeful moment for a population of whales that has survived against all odds.

Hindered by poor visibility, Richard used a polecam to photograph the whales gradually moving towards his boat. Pushing his camera to its limits in the dark water, he was relieved to find the image pin-sharp and the moment of copulation crystalized in time.

When ready to mate, the female southern right whale rolls onto its back, requiring the male to reach its penis across the female’s body. Known by the Māori as tohorā, the New Zealand population was hunted to near extinction in the 1800s, so every new calf offers new hope.

“Shooting star” by Tony Wu (USA/Japan). Winner, Underwater.

Tony Wu watches the electrifying reproductive dance of a giant sea star.

As the surrounding water filled with sperm and eggs from spawning sea stars, Tony faced several challenges. Stuck in a small, enclosed bay with only a macro lens for photographing small subjects, he backed up to squeeze the undulating sea star into his field of view, in this galaxy-like scene.

The ‘dancing’ posture of spawning sea stars rising and swaying may help release eggs and sperm, or may help sweep the eggs and sperm into the currents where they fertilize together in the water.

“House of bears” by Dmitry Kokh (Russia). Winner, Urban Wildlife.

Dmitry Kokh presents this haunting scene of polar bears shrouded in fog at the long-deserted settlement on Kolyuchin.

On a yacht, seeking shelter from a storm, Dmitry spotted the polar bears roaming among the buildings of the long-deserted settlement. As they explored every window and door, Dmitry used a low-noise drone to take a picture that conjures up a post-apocalyptic future.

In the Chukchi Sea region, the normally solitary bears usually migrate further north in the summer, following the retreating sea ice they depend on for hunting seals, their main food. If loose pack ice stays near the coast of this rocky island, bears sometimes investigate.

“Heavenly flamingos” by Junji Takasago (Japan). Winner, Natural Artistry.

Junji Takasago powers through altitude sickness to produce a dream-like scene.

Junji crept towards the preening group of Chilean flamingos. Framing their choreography within the reflected clouds, he fought back his altitude sickness to capture this dream-like scene.

High in the Andes, Salar de Uyuni is the world’s largest salt pan. It is also one of Bolivia’s largest lithium mines, which threatens the future of these flamingos. Lithium is used in batteries for phones and laptops. Together we can help decrease demand by recycling old electronics.

“A theatre of birds” by Mateusz Piesiak (Poland). Winner, Rising Star Portfolio Award.

Placing his remote camera on the mud of the reed bed, Mateusz seized the opportunity to capture the moment when a passing peregrine falcon caused some of the dunlins to fly up.

Mateusz Piesiak carefully considered camera angles to produce a series of intimate photographs exploring the behavior of birds.

Winner of the Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year award when he was 14, Mateusz explored his locality during the Covid-19 lockdown. ‘Even a small pond or park in the city center turned out to be a very good place for photographing wildlife.’

Throughout this portfolio Mateusz focuses on local birds, researching and preparing for images that were in his mind ‘for days, months or even years before he finally managed to realize them.

The winners will see their photos go into an exhibition at the UK’s Natural History Museum.

“Out of the fog” by Ismael Domínguez Gutiérrez (Spain). Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year Winner, 11-14 Years.

Ismael Domínguez Gutiérrez reveals a monochromatic scene as an osprey sits on a dead tree, waiting for the fog to lift.

When Ismael arrived at the wetland, he was disappointed not to be able to see beyond a few meters—and certainly he had no hope of glimpsing the grebes he wanted to photograph. But as the fog began to lift, it revealed the opportunity for this striking composition.

Ospreys are winter visitors to the province of Andalucía. Here the many reservoirs offer these widespread fish‑eating raptors shallow, open water that is clearer than many rivers and lakes.

“Battle stations” by Ekaterina Bee (Italy). Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year Winner, 10 Years and Under

Ekaterina Bee watches as two Alpine ibex spar for supremacy.

It was near the end of a spring day trip with her family that Ekaterina spotted the fight. The two ibex clashed horns and continued to trade blows while standing on their hind legs like boxers in a ring.

In the early 1800s, following centuries of hunting, fewer than 100 Alpine ibex survived in the mountains on the Italy–France border. Successful conservation measures mean that, today, there are more than 50,000.

“The listening bird” by Nick Kanakis (USA). Winner, Behavior: Birds.

Nick Kanakis gains a glimpse into the secret life of wrens.

Nick spotted the young gray-breasted wood wren foraging. Knowing it would disappear into the forest if approached, he found a clear patch of leaf litter and waited. Sure enough, the little bird hopped into the frame, pressing its ear to the ground to listen for small insects.

This prey-detecting technique is used by other birds, including the Eurasian blackbird. Grey-breasted wood wrens are ground-dwelling birds, often heard but not seen. They broadcast loud, melodious songs and rasping calls while hidden in the undergrowth.

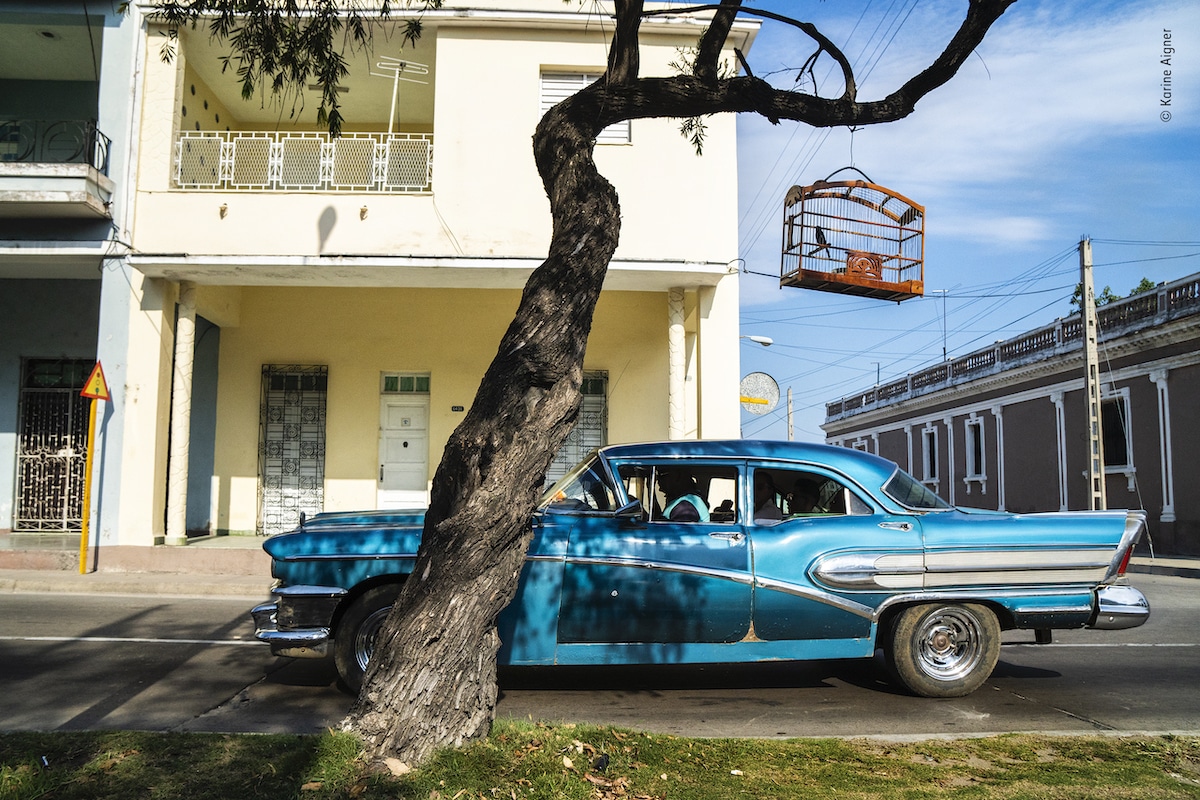

“The Cuban connection” by Karine Aigner (USA).

Winner, Photojournalist Story Award.

A Cuban bullfinch is positioned alongside a road so that it becomes accustomed to the hubbub of street life and therefore less likely to be distracted during a competition. These birds are highly prized for their sweet voice and feisty spirit.

Karine Aigner explores the relationship between Cuban culture and songbirds, and the future of a deep-rooted tradition.

For hundreds of years, some Cubans have caught and kept songbirds and held bird-singing contests. Throughout a turbulent period of economic sanctions and political unrest, these small, beautiful birds have provided companionship, entertainment and friendly competition within the community.

Now with regular travel and emigration between Cuba and North America, the tradition of songbird contests has crossed an ocean. As songbird populations plummet, US law enforcement is cracking down on the trapping, trading and competing of these birds.

“Puff perfect” by José Juan Hernández Martinez (Spain). Winner, Animal Portraits.

José Juan Hernández Martinez witnesses the dizzying courtship display of a Canary Islands houbara.

José arrived at the houbara’s courtship site at night. By the light of the moon, he dug himself a low hide. From this vantage point he caught the bird’s full puffed-out profile as it took a brief rest from its frenzied performance.

A Canary Islands houbara male returns annually to its courtship site to perform impressive displays. Raising the plumes from the front of its neck and throwing its head back, it will race forward before circling back, resting just seconds before starting again.

“Ndakasi’s passing” by Brent Stirton (South Africa). Winner, Photojournalism.

Brent Stirton shares the closing chapter of the story of a much-loved mountain gorilla.

Brent photographed Ndakasi’s rescue as a two-month-old after her troop was brutally killed by a powerful charcoal mafia as a threat to park rangers. Here he memorialized her passing as she lay in the arms of her rescuer and caregiver of 13 years, ranger Andre Bauma.

As a result of unrelenting conservation efforts focusing on the daily protection of individual gorillas, mountain gorilla numbers have quadrupled to over 1,000 in the last 40 years.

“The magical morels” by Agorastos Papatsanis (Greece). Winner, Plants and Fungi.

Agorastos Papatsanis composes a fairy tale scene in the forests of Mount Olympus.

Enjoying the interplay between fungi and fairy tales, Agorastos wanted to create a magical scene. He waited for the sun to filter through the trees and light the water in the background, then used a wide-angle lens and flashes to highlight the morels’ labyrinthine forms.

Morels are regarded as gastronomic treasures in many parts of the world because they are difficult to cultivate, yet in some forests they flourish naturally.