Looking Southwest from Hebo Mountain East Point, Siuslaw (1936).

Historic panoramic photograph from U.S. Forest Service, held by National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, WA. Scanned by John F Marshall with financial assistance of Oregon Department of Forestry through Oregon Field Office of The Nature Conservancy. Photographs referred to as Osborne Panoramas.

With almost half of both Oregon and Washington State’s landmass covered with forests, careful management of this resourceful landscape has always been of paramount importance. And, of course, fire management has long been a duty of the Forest Service in both states. Between 1933 and 1935, the Oregon and Washington Forest Services carried out a landmark project, collecting panoramic photographs from every fire lookout in the region.

Collectively called the Osborne Panoramas, a crew of three to six people—led by pioneering Oregon Forest Service employee W.B. Osborne—carried a 75-pound custom built camera across 813 sites in order to record these vital images. At the time, the goal of the project was to increase fire suppression effectiveness by aiding communication between fire lookouts and ranger stations. Now, these images are a valuable resource for understanding how the ecosystem of the area has developed in the 85 years since the original project.

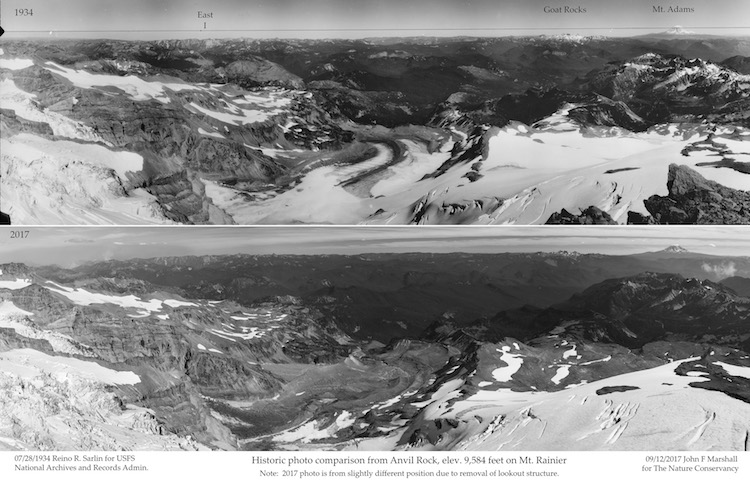

Historic photo comparison from Anvil Rock, elevation 9.584 feet on Mt. Rainier. Top: Reino R. Sarlin for USFS National Archives and Records Admin (1934). Bottom: John F. Marshall for The Nature Conservancy Washington (2017).

In fact, photographer John Marshall has been working to reshoot panoramas of select sites. In some cases, this has proven to be quite complicated. Some of the lookout towers are now gone, others have trees blocking what would have been a clear view. But thanks to Marshall’s diligent work—he also scanned a good portion of the original panoramas at the National Archive in Seattle—it’s possible to see how time has changed America’s forests. One view from 9,500 feet on Mount Ranier clearly shows the disappearing Paradise Glacier in the center of the image.

We had a chance to speak with Bryce Kellogg of The Nature Conservancy Oregon about the history of the Osborne Panoramas, their importance, and what we can learn from them today. Read on for our exclusive interview and see all of the Osborne Panoramas on The Nature Conservancy’s website.

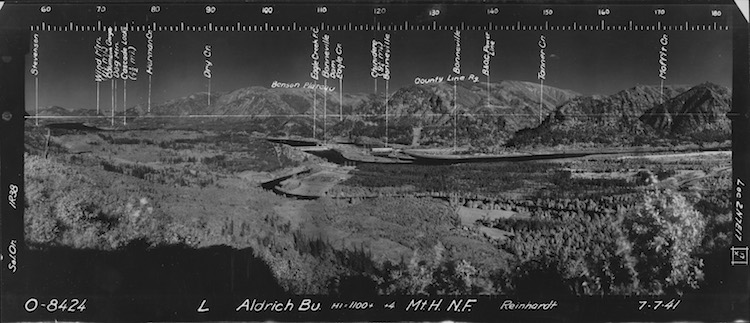

Looking Southeast from Aldrich, Mt. Hood (1941).

Historic panoramic photograph from U.S. Forest Service, held by National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, WA. Scanned by John F Marshall with financial assistance of Oregon Department of Forestry through Oregon Field Office of The Nature Conservancy. Photographs referred to as Osborne Panoramas.

Can you tell us more about W.B. Osborne and his importance as an innovator?

W.B. Osborne graduated from the Yale School of forestry in 1909 and immediately started working for the Forest Service on the Mount Hood National Forest. His most lasting invention was the Osborne fire finder, which is still in use. He also designed a backpack-pump for carrying and spraying water while fighting forest fires, versions of which are still in use. Besides his physical inventions, Osborne was truly pioneering in his collection and analysis of detailed geographic information to aid decision making. Many of the procedures he used are easily recognizable by today’s analysts. And even more impressive since they were done by hand.

Looking Southeast from South Saddle Mountain, Tillamook Burn (1935).

Historic panoramic photograph from U.S. Forest Service, held by National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, WA. Scanned by John F Marshall with financial assistance of Oregon Department of Forestry through Oregon Field Office of The Nature Conservancy. Photographs referred to as Osborne Panoramas.

How were the Osborne Panoramas used by the Forest Service?

The images were originally used for two purposes. The primary use was communication between the fire lookout and the ranger station coordinating fire activity. Fire-lookouts at the time had land telephone lines connected to a Forest Service ranger station. Both the lookout and the ranger station had copies of the photo so the lookout using the azimuth marking on the top of the photo and the elevation markings on the side could communicate to the station where they saw smoke. This was in addition to the more precise angle measurements that were taken with the fire finder.

The second purpose was a systematic mapping of what parts of the landscape lookouts could see. The crew that collected the photos in the summer, spent the winter in the office mapping what parts of the landscape were visible from each lookout. Combining these maps from multiple lookouts the Forest Service could discover areas where they didn’t have adequate surveillance. This type of mapping would be called a viewshed analysis today and requires sophisticated software, this is the only time I have ever heard of someone performing this extensive an analysis by hand.

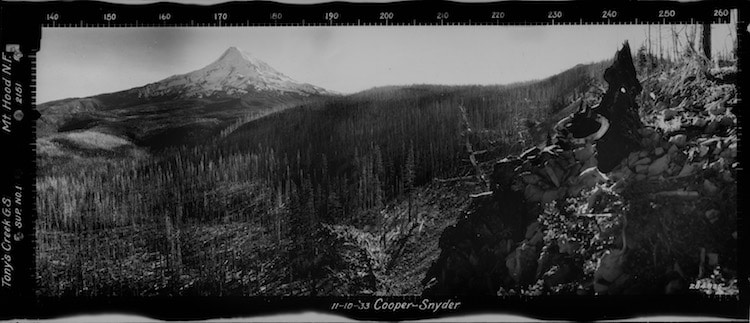

Looking Southwest from Tony Creek G.S., Mt. Hood (1933).

Historic panoramic photograph from U.S. Forest Service, held by National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, WA. Scanned by John F Marshall with financial assistance of Oregon Department of Forestry through Oregon Field Office of The Nature Conservancy. Photographs referred to as Osborne Panoramas.

What do the panoramas from the 1930s tell us about how the ecosystem in Oregon and Washington has changed?

First, the panoramas show us that forests change, a lot. It is easy to imagine that wild places are timeless. But, forests have a history. They live, die, and regrow on timescales longer than our memory. This makes it difficult to appreciate the effects of time and our management.

The photos have the advantage that they are specific. Each part of the forest has a unique story of fire, timber harvest, and insects. I do see two general trends in the photos.

First, in the cooler wetter forests at high elevations and west of the Cascade mountains, the photos often show large areas of forest which burned in the early 1900’s. The photo showing the south side of Mount Hood is a good example. These large fires led to the Forest Service’s policy of aggressive fire suppression.

Second, in the dry fire-adapted forests east of the Cascades the old photos show a forest of large fire-resistant trees. The forest has an intricate pattern, there clumps and induvial trees with many small openings. In many of the photos, the differences between dry south-facing slopes and cooler north-facing slopes are very clear. Because of fire suppression and past logging, these forests today are much denser with younger fire-intolerant trees having grown up into the gaps.

These dry forests were historically maintained by frequent low severity fires that kill very few trees. Often these low severity fires were intentionally lit by Native Americans to improve hunting and favor desired food plants. This new dense forest is very vulnerable to uncharacteristic high severity fire which kills both the old growth ponderosa pines and the younger fir trees that have grown up in the absence of fire.

Looking North from Marys Peak Point , Siuslaw (1937). Historic panoramic photograph from U.S. Forest Service, held by National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, WA. Scanned by John F Marshall with financial assistance of Oregon Department of Forestry through Oregon Field Office of The Nature Conservancy. Photographs referred to as Osborne Panoramas.

Why is this important for the public to understand?

It is important for the public to understand that fire is a natural part of forests in Oregon and Washington. Forests change over time and our management has had large effects some of which were unintentional. We will choose what our forests look like in the future and these historic photos serve as a good guide for what is possible.

The large fires this year and over the last decade in the Pacific Northwest show that a policy of simple aggressive fire suppression is no longer effective. The panoramas and the project they were a part of show how innovative, ambitious, and dedicated early Forest Service managers where. They were confronted with a problem of large destructive fires and set out to solve it using all the resources they could muster. Their efforts were remarkably successful for a time, but the forests they were protecting were still changing. And often becoming more vulnerable to the fire they were trying to stop.

Today we can take inspiration from these early mangers creativity and resolve but, will need to use our deeper knowledge of forest ecology and fire to develop new solutions. An example of these new approaches is careful thinning in dry forests to restore spatial pattern and species composition. Allowing for the reintroduction of prescribed fire and which builds the forest resilience to future natural fires.

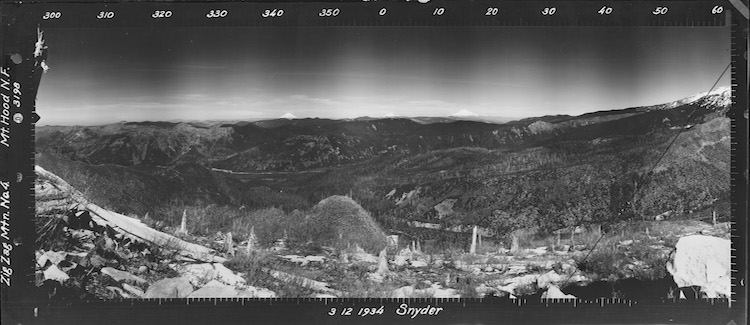

Looking North from Zig Zag East, Mt. Hood (1934). Historic panoramic photograph from U.S. Forest Service, held by National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, WA. Scanned by John F Marshall with financial assistance of Oregon Department of Forestry through Oregon Field Office of The Nature Conservancy.

Looking north from Abbott Butte (1933).

Historic panoramic photograph from U.S. Forest Service, held by National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, WA. Scanned by John F Marshall with financial assistance of Oregon Department of Forestry through Oregon Field Office of The Nature Conservancy. Photographs referred to as Osborne Panoramas.

The Nature Conservancy Oregon: Website | Facebook | Instagram

My Modern Met granted permission to use photos by The Nature Conservancy Oregon and John Marshall.

Related Articles:

Interview: Fire Photographer Documents the Bravery of Firefighters Battling Massive Flames

National Geographic Photographer’s Stunning Landscapes Pay Tribute to Ansel Adams

Tree-Planting Drones Are Helping Replant Our Forests by Seeding 100,000 Plants a Day

Firefighter’s Remarkable Instagram Shows Us How Intense the Action Is