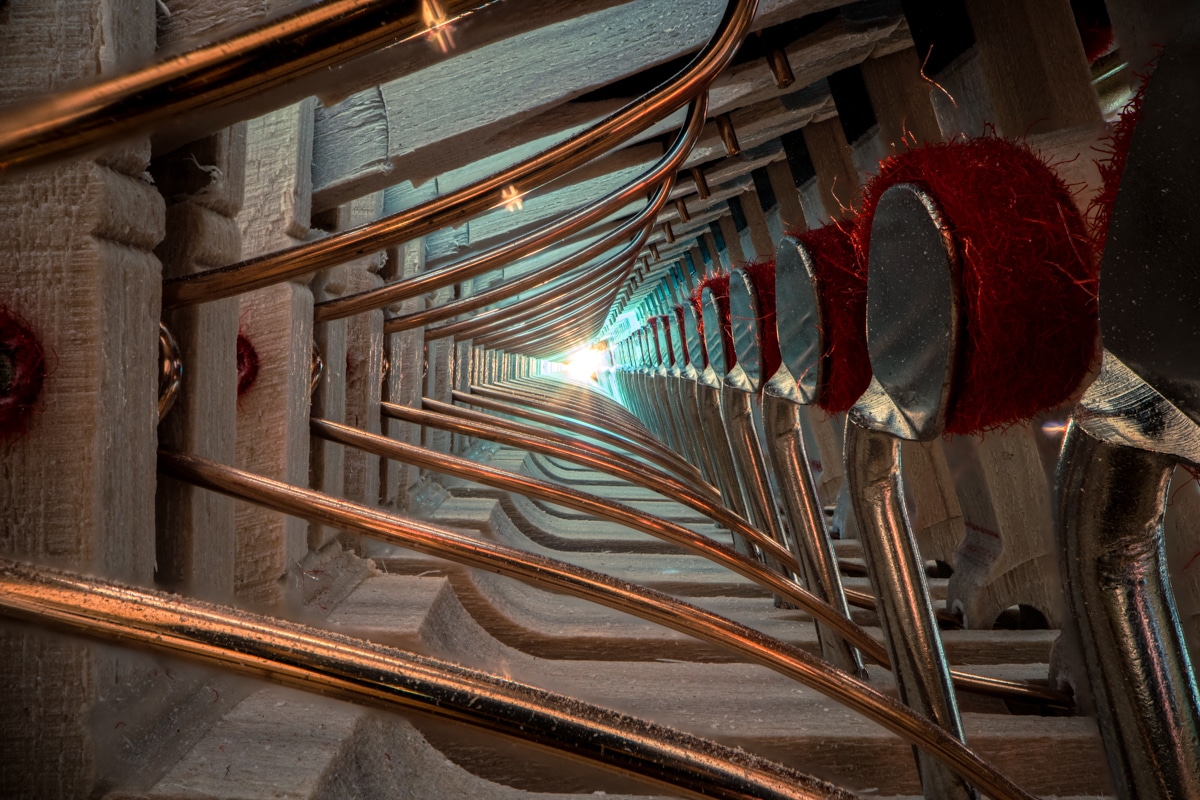

c. 1780 Cello by Lockey Hill

If you look quickly at Charles Brooks‘ photographs, you might think that he’s an adventurer documenting abandoned buildings. But upon closer observation, one notes something a bit different about these cavernous spaces and tunnels. They aren’t, in fact, buildings but the interiors of classical musical instruments that Brooks photographs for his project Architecture in Music.

The series is a culmination of Brooks’ past and present lives, as he worked as a concert cellist for 20 years before starting his career as a professional photographer. This look “under the hood” of instruments that he’s familiar with allows him to satisfy his curiosity as a musician and get creative as a photographer.

“The interior of a cello or violin was only something you only saw when being repaired. The intricate complexity of a piano’s action was hidden behind thick lacquered wood. It was always a thrill to see inside them during a rare visit to a luthier,” Brooks tells My Modern Met. “Exploring the inner workings of these instruments came naturally as soon as I was able to get my hands on the probe lenses necessary to photograph the instruments without damage.”

Creatively, Brooks used a focus stacking effect in an innovative manner to make these small spaces seem quite large. Achieving the effect, while keeping everything sharp, was quite difficult. “None of the series are a single shot,” Brooks reveals. “It is impossible to have such clear focus in a single frame. Instead, I take dozens to hundreds of images from the same position, slowly shifting the focus from front to back. Those frames are then carefully blended into a final shot where everything is clear. The result fools the brain into believing that it’s looking at something large or cavernous. I like the duality that the instrument’s interior appears to be its own concert hall.”

As Brooks began the series, he was surprised by what he saw inside. Each instrument has its own story to tell, with repair and tool marks showing its history. From an 18th-century cello to a modern saxophone, these musical instruments are distinct in their features. By peering into them, Brooks was able to gain a new appreciation for the craftsmanship and engineering behind the design.

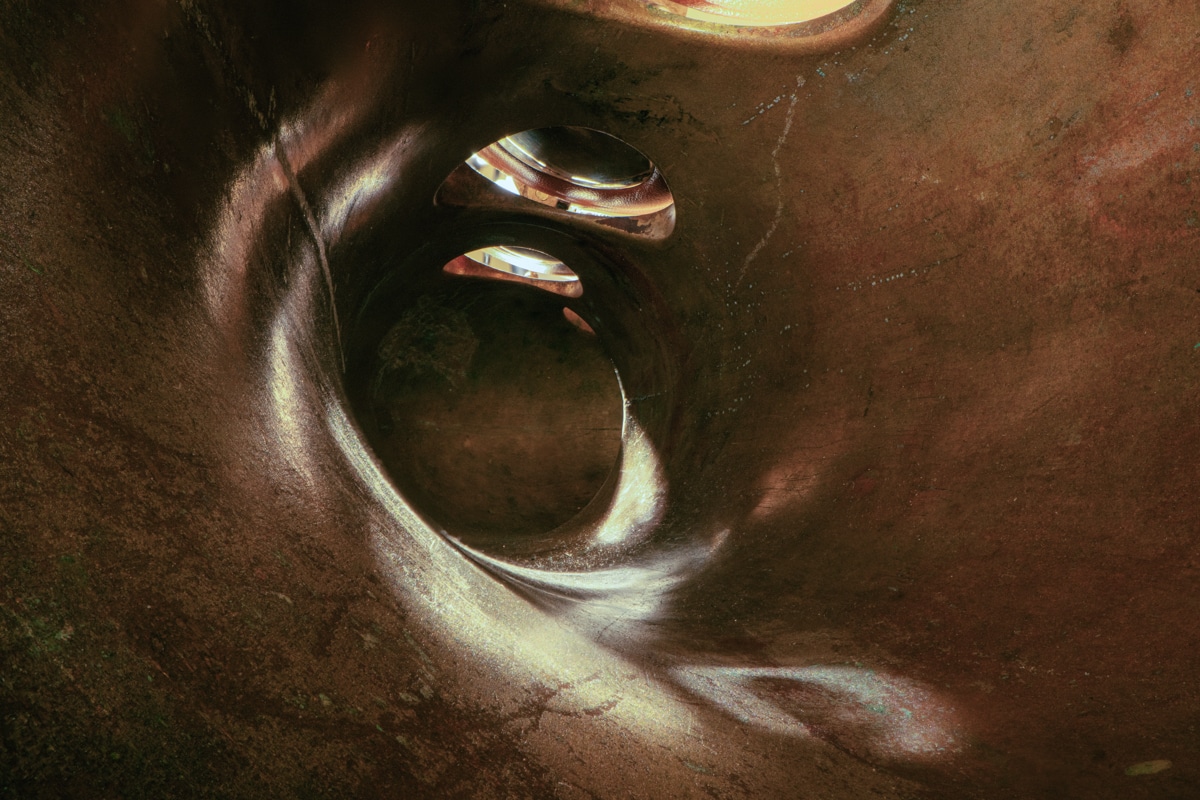

“I expected to see a bigger difference between the pianos—Steinway and Fazioli—each of which cost hundreds of thousands. I think their striking similarity, even at such a macro level, is a testament to the mechanics of a piano action having reached a certain perfection in design. But the biggest surprise had to be the didgeridoo. I wasn’t aware that they are carved out by termites, not by hand! The organic surface is so alien, I find it quite mesmerizing.”

Brooks hopes that his photographs will allow music-lovers to gain a new appreciation not only for musicians but for the entire chain of experts who dedicate themselves to crafting these instruments.

Architecture in Music is a fascinating look at the interiors of classical musical instruments.

Fazioli Grand Piano

Steinway Model D Grand Piano

Steinway Model D Grand Piano

Using focus stacking, photographer and former concert cellist Charles Brooks creates the illusion of grand spaces.

Fazioli Grand Piano

14k Rose Gold Flute

Often, he compares modern and antique instruments, like these three saxophones.

1940s Selmer Balanced Action Saxophone

1980s Yanagisawa Saxophone

2021 Selmer Saxophone

One of his biggest surprises was a didgeridoo, as the interior is carved out by termites.

Australian Didgeridoo by Trevor Gillespie Peckham