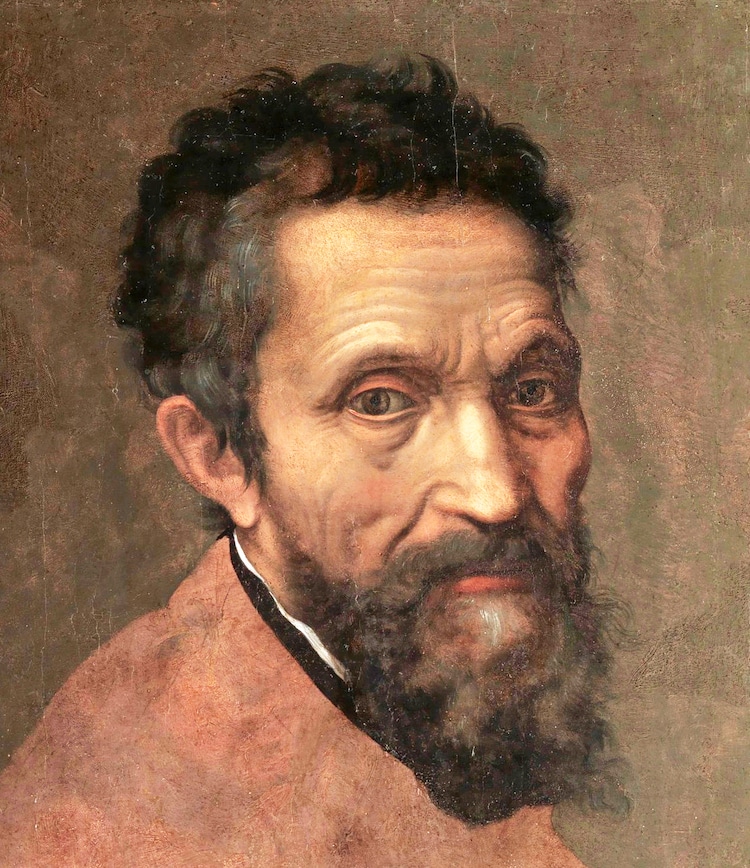

Daniele da Volterra, “Portrait of Michelangelo,” c. 1544 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase, My Modern Met may earn an affiliate commission. Please read our disclosure for more info.

One of the greatest artists of all time, Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) enjoyed unparalleled success both during and after his lifetime. Along with Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Titian, he is considered the exemplary figure of the Italian Renaissance and millions flock to see his work in Italy each year.

From his iconic David sculpture to his breathtaking frescos in the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo has been making history for centuries. His nickname Il Divino (‘The Divine One”) shows just how beloved he was and his success is significant in a time when most artists did not enjoy wealth or fame while they were alive. In fact, Michelangelo is the first Western artist to have a biography published during his lifetime.

For centuries we’ve admired his art, but the man behind the art is just as fascinating. For much of the 16th century, he defined Italian art and culture, casting a shadow that would influence artists for generations to come. Let’s learn more about the man who once wrote, “The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.”

Learn 10 facts you may not know about world-famous sculptor Michelangelo.

He grew up near a marble quarry.

Michelangelo, “Madonna of the Stairs,” 1491 (Photo: Sailko via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

When he was 6 years old, Michelangelo was moved to the Tuscan town of Settignano where his father owned a marble quarry. It was during this time that he developed a passion for the material that would last his whole life.

In his Lives of the Artists, Renaissance art historian Giorgio Vasari quoted Michelangelo as saying, “If there is some good in me, it is because I was born in the subtle atmosphere of your country of Arezzo. Along with the milk of my nurse, I received the knack of handling chisel and hammer, with which I make my figures.”

Another sculptor broke his nose.

When Michelangelo was 17, another young sculptor named Pietro Torrigiano broke his nose after Michelangelo made a sharp comment. The injury was so severe, that it left Michelangelo’s nose permanently disfigured.

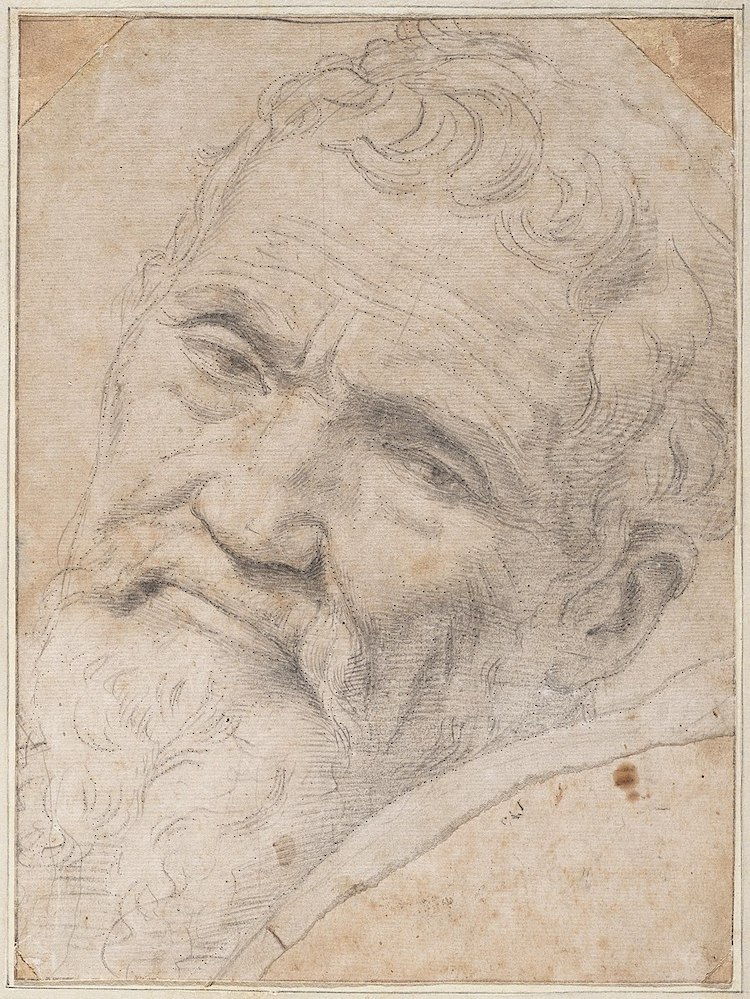

Daniele da Volterra, “Portrait of Michelangelo,” c. 1548–1553 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, PD-US)

Torrigiano was quoted as saying, “It was Buonarroti’s habit to banter all who were drawing there; and one day, among others, when he was annoying me, I got more angry than usual, and clenching my fist, gave him such a blwo on the nose, that I felt bone and cartilage go down like a biscuit beneath my knuckles; and this mark of mine he will carry with him to the grave.”

Michelangelo and Torrigiano were both studying under the patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici at the time, so after the incident, Torrigiano fled Florence to escape the consequences from Lorenzo de’ Medici, who was apparently furious that his artist was assaulted.

He first gained attention for committing art fraud.

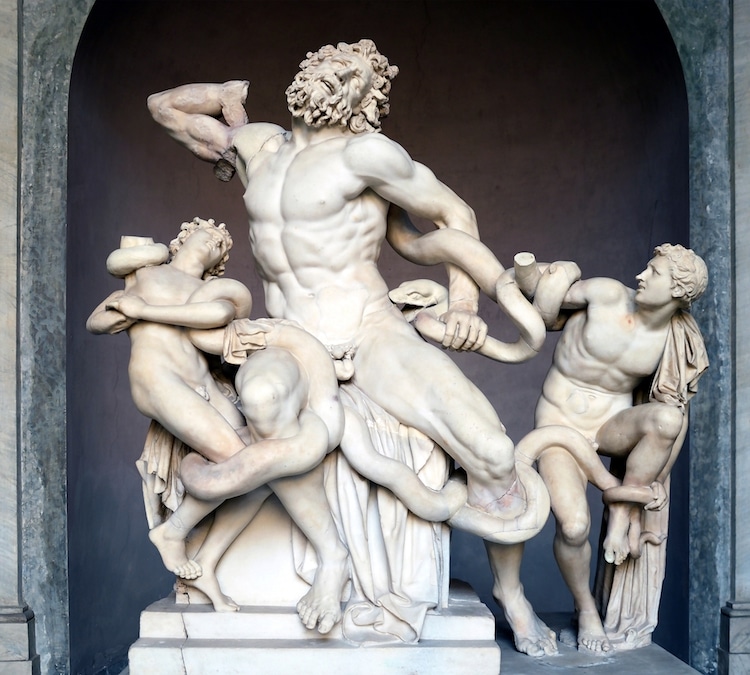

It was once rumored that the famed “Laocoon and His Sons” sculpture was also a forgery by Michelangelo (Photo: LivioAndronico via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

As a young sculptor, Michelangelo caught the attention of some important patrons by passing off one of his own works as an antique from ancient Greece. When he was just 19 years old, he sculpted a now-lost Sleeping Cupid and then worked with a member of the powerful Medici family to make it seem like an antique. The young artist even buried the marble sculpture and dug it up so that it would seem old and worn. While this allowed him to sell the sculpture for a higher price, it also caught the eye of an important collector.

During the Italian Renaissance, copying classic works of art wasn’t seen as a bad thing, but rather a demonstration of talent. So when Cardinal Raffaele Riario, who had purchased the work, discovered the forgery, he wasn’t upset. Rather, he invited Michelangelo to come to Rome and work for him. It was an invitation that launched Michelangelo’s career.

He was a poet.

It’s #WorldPoetryDay! These pages from one of Michelangelo’s sketchbooks feature five drafts of poems dating from 1501–1505. There are just under 2 weeks left to see our FREE Michelangelo display in gallery 8, open until 2 April. Booking recommended: https://t.co/6m0GMKjEfq pic.twitter.com/s24oX17A6Z

— Ashmolean Museum (@AshmoleanMuseum) March 21, 2018

In true “Renaissance Man” fashion, Michelangelo wasn’t merely a sculptor, painter, and architect. He was also an acclaimed poet, writing hundreds of sonnets and madrigals. Written in a type of letter format, his poems were often addressed to friends and contained musings about love—toward both men and women.

In fact, due to the homoerotic nature of some of the poetry, the genders were replaced when his work was published posthumously in the 17th century. Later translations in English included the original pronouns and Michelangelo’s poems were particularly popular during the Victorian era. Princeton University Press’ Poems and Letters includes a selection of the artist’s poems about love and religion.

His most famous sculpture was made with a piece of discarded marble.

Michelangelo, “David,” 1501–1504 (Photo: Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

Michelangelo’s David sculpture is a 17-foot-tall masterpiece that has become a symbol of Italian Renaissance art. Made to adorn the roof of the Florence Cathedral, the sculpture’s oversize proportions ensured that it would be eye-catching from a distance, but working with marble was no easy task, as the material was expensive and easy to crack if not in the hands of the right artist. The marble used to create David has an interesting history itself.

The block was nicknamed “The Giant” for its immense size and had originally been brought in for another artist to create an artwork for the church. For reasons unknown, that artist barely started—and never finished—the sculpture and the marble languished in the church’s yard. It remained unused for nearly 40 years when church officials decided it was a waste to leave it outside. While many artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, were brought in to evaluate the marble block, it was the young Michelangelo who was entrusted with “The Giant.” He was just 26 years old at the time.

He didn’t like signing his work.

Michelangelo, “The Pietà,” 1498–1499 (Photo: Stanislav Traykov, Niabot (cut out) via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Interestingly, Michelangelo only signed one artwork with his name and it was his first public commission. After coming to Rome, he was asked to create The Pietà. This scene, which depicts the Virgin Mary mourning the loss of Jesus Christ, who is laid across her lap, was completed in 1499 and is now in St. Peter’s Basilica. To show his pride in the work, Michelangelo included a sash across the chest of the Virgin Mary, which seems to have no other purpose other than to include his name.

The sash reads, “MICHAELA[N]GELUS BONAROTUS FLORENTIN[US] FACIEBA[T](Michelangelo Buonarroti, Florentine, made this).” Michelangelo’s biographer, Giorgio Vasari, said that the artist added the signature after the work was finished when he flew into a jealous rage after overhearing someone attributing the work to another artist. It was something he supposedly later regretted, vowing to never sign another work.

He often included self-portraits in his art.

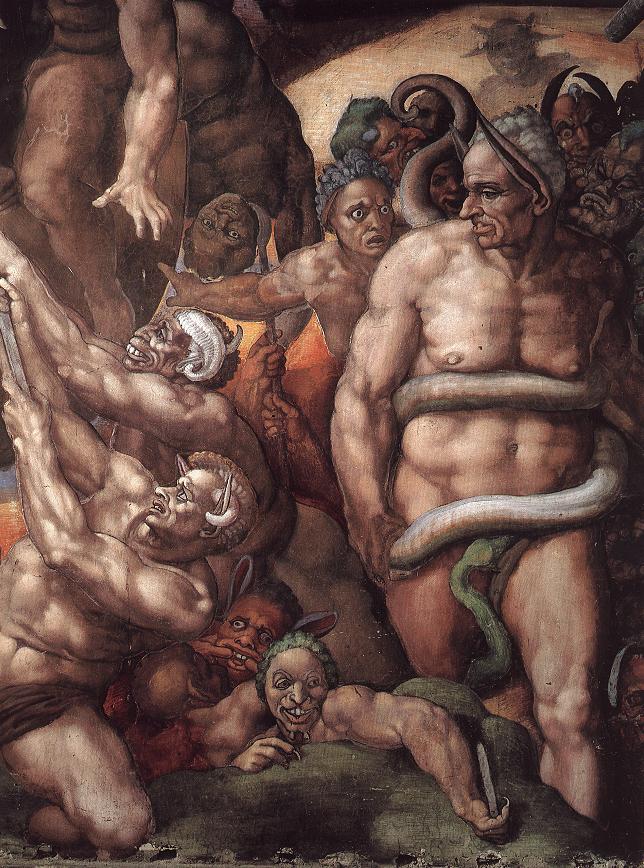

Detail of “The Last Judgement” showing Saint Bartholomew displaying his flayed skin, with the face of Michelangelo (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, PD-US)

Even though he didn’t like signing his artwork, Michelangelo found other ways to include a piece of himself in his creations. Several of his paintings include self-portraits, including The Last Judgement where his face was used to represent Saint Bartholomew on a piece of flayed skin.

He wasn’t always easy to get along with.

Michelangelo’s incredible creative vision and perfectionist mentally made him a celebrated artist even during his lifetime, but these same characteristics also drove people mad. Unlike more affable artists like Raphael, who was painting the famed School of Athens while Michelangelo worked on the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo wasn’t the easiest person to get along with. This is perhaps why he didn’t have a large studio of assistants, which was the norm at the time, preferring to do the heavy lifting himself.

This is also why he wasn’t afraid to stand up to important figures when he felt it threatened his creativity. That included Pope Julius II, who forced the sculptor to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling instead of focusing on the Pope’s tomb sculptures—something Michelangelo greatly preferred. After leaving Rome for Florence to get a break from the pressures of the job, Michelangelo wrote, “Now if His Holiness wants to go on with it, he should place the deposit for me here in Florence and I’ll write to tell him where. And I have many marbles on order in Carrara which I shall have brought here along with those I have in Rome. Even if it meant a serious loss to me, I shouldn’t mind so long as I could do the work here.”

It also wasn’t wise to cross Michelangelo. When a church official criticized his work during a preview of the artist’s acclaimed Last Judgement fresco, he discovered an unwelcome surprise in the final artwork. In an act of revenge, Michelangelo used the official’s face on the figure of Minos.

Detail of “The Last Judgement” with Biagio da Cesena as Minos by Michelangelo, 1536–1541 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, PD-US)

This creature, which resided in Hell, was the judger of souls and is depicted with two donkey ears and a serpent biting his genitals. Although the official complained to the pope, he was calmly told that the pope’s jurisdiction didn’t extend into hell.

He worked for nine different popes.

Raphael, “Portrait of Pope Julius II, in the Mass at Bolsena,” 1512 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, PD-US)

Over the course of his lifetime, Michelangelo worked for nine different popes: Pope Julius II (papacy: 1503–1513), Pope Leo X (papacy: 1513–1521), Adrian VI (papacy: 1522–1523), Clement VII (papacy: 1524–1534), Paul III (papacy: 1534–1549), Julius III (papacy: 1550–1555), Marcellus II (papacy: 1555), Paul IV (papacy: 1555–1559), and Pius IV (1559–1565).

These relationships produced a range of works, from the Sistine Chapel ceiling under Julius II to the Laurentian Library for Clement VII to The Last Judgment fresco under Pius IV.

He was a workaholic, but it paid off.

Michelangelo, “Rondanini Pietà,” 1594 (Photo: Paolo da Reggio via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

“Many believe —and I believe—that I have been designated for this work by God. In spite of my old age, I do not want to give it up; I work out of love for God and I put all my hope in Him.”

Michelangelo lived a long life, passing away at age 88. As he got older, he never slowed down and spent the last decades of his life as the architect of St. Peter’s Basilica—sending notes to workers when he was too weak to go on site. While that position occupied much of his time, he continued sculpting. In fact, he was working on the Rondanini Pietà, which is now in Milan, up until six days before his death.

As such a famous artist with a long career, it should come as no surprise that Michelangelo died a wealthy man. He worked for nine different Catholic Popes, a huge feat considering most leaders wished to change up artists when they took power. Upon his death, he left an estate valued at 50,000 Florins—the equivalent of between $35 and $50 million today. Interestingly, for as wealthy as he was, Michelangelo didn’t act like it. It’s said that he hated bathing and prided himself on continuing to live a humble life despite his fortune.

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

The Significance of Botticelli’s Renaissance Masterpiece ‘Primavera’

9 Renaissance Artists Whose Work Transformed the Art World

Leonardo Da Vinci’s To-Do List Proves He’s a True Renaissance Man

Here’s Where 20 of Art History’s Most Famous Masterpieces Are Located Right Now