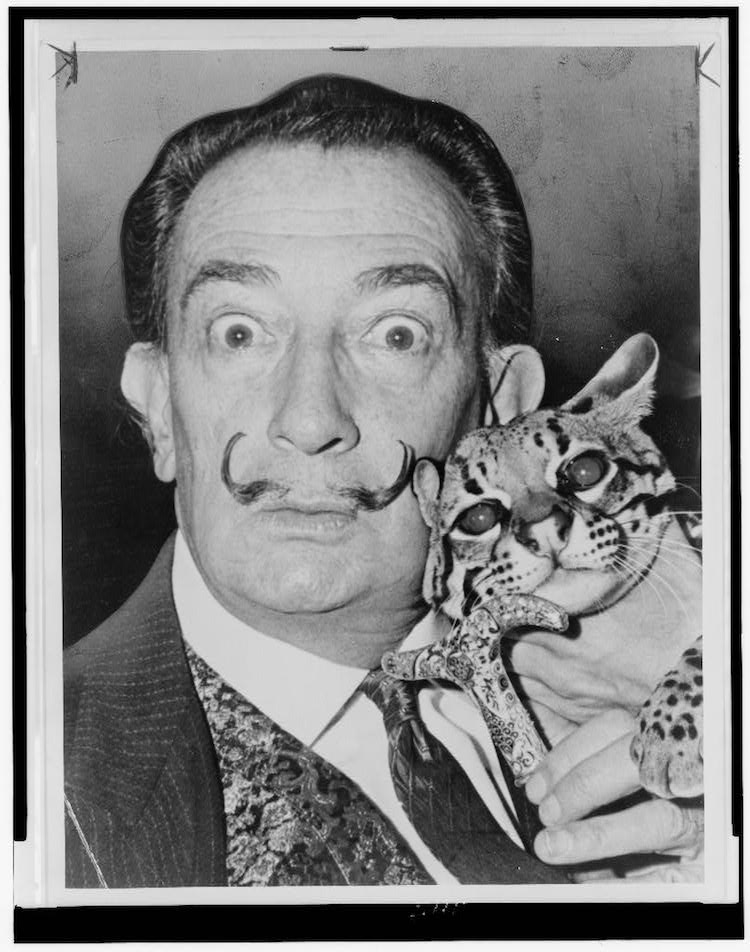

Salvatore Dali with ocelot friend at St Regis, 1965. (Photo: Roger Higgins / Library of Congress)

With a career that spanned more than six decades, Salvador Dalí is undoubtedly one of the most influential figures in modern art. Upon his death in 1989, he’d created an astonishing legacy that not only includes his most famous Surrealist paintings, but sculpture, film, photography, and much more.

As an eccentric figure from childhood, Dalí loved to push the boundaries—both in his personal and professional life. And he was also a hustler and master of self-promotion. Let’s look at just some of the interesting facts about Dalí’s life, some of which may surprise you.

|

Full Name

|

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech

|

|

Born

|

May 11, 1904 (Figueres, Spain)

|

|

Died

|

January 23, 1989 (Figueres, Spain)

|

|

Notable Artwork

|

The Persistence of Memory

|

|

Movement

|

Surrealism

|

Here are 20 facts about Salvador Dalí, the eccentric master of Surrealism, that you may not know.

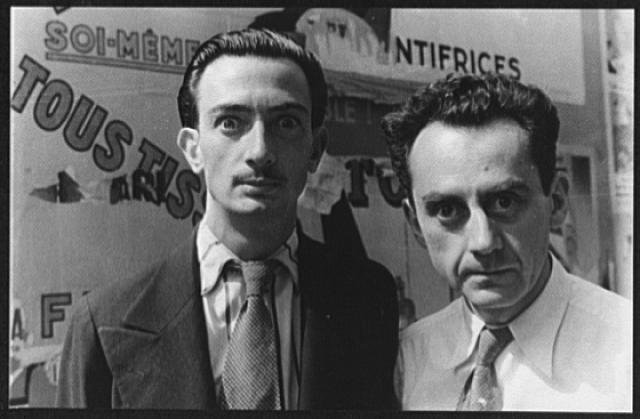

Photograph of Salvador Dalí, 1934 (Photo: Carl Van Vechten / Library of Congress)

He believed he was a reincarnation of his dead brother.

Dalí wasn’t the only Salvador in his family. Not only was his father named Salvador, but so was his older brother. Dalí’s brother died just nine months before the artist was born. When the famed artist was 5 years old, his parents took him to his brother’s grave and told him that he was his brother’s reincarnation. It was a concept that Dalí himself believed, calling his deceased sibling “a first version of myself but conceived too much in the absolute.” His older brother would become prominent in Dalí’s later work, like the 1963 Portrait of My Dead Brother.

He started painting as a young child.

Dalí’s earliest known painting was produced in 1910 when he was just 6 years old. Titled Landscape of Figueres, the oil-on-postcard scene depicts the lush green hills and mountainous backdrop of his Catalonia hometown, Figueres. The impressive piece reveals the iconic artist’s incredible, natural-born talent at such a young age. It now hangs in the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida.

He was expelled from art school (twice).

Proving that he was a rebel from the start, Dalí was expelled from art school—not once, but twice. Young Dalí’s artistic talent was fostered from a young age, particularly by his mother, who passed away when he was just 16 years old. While studying at the Fine Arts Academy in Madrid, he was known for his eccentric behavior and dress, which was that of a 19th-century British dandy. Unfortunately, Dalí never graduated. His first expulsion came in 1923, for his role in a student protest. After returning to the school, he faced a second expulsion just before his final exams in 1926.

In his 1942 autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, the artist wrote that he was expelled because he wouldn’t sit for his oral exams. “I am infinitely more intelligent than these three professors, and I therefore refuse to be examined by them. I know this subject much too well.” But the expulsion didn’t slow him down, that same year he traveled to Paris for the first time and met his idol, Pablo Picasso.

Photograph of Salvador Dalí and Man Ray in Paris, 1934 (Photo: Carl Van Vechten / Library of Congress)

He didn’t do drugs.

While Dalí’s surreal artwork and eccentric behavior may have you think otherwise, the artist did not use any chemical substances to alter his state. In fact, he once famously stated, “I don’t do drugs, I am drugs.” To spur his creativity, in the early 1930s he developed something called the paranoiac-critical method. This allowed him to access his subconscious and was a major contribution to the Surrealist movement. One way he kept himself in a dreamlike state included staring fixedly at a particular object until it transformed into another form, sparking a sort of hallucination.

He created The Persistence of Memory when he was 28.

With its strange subject matter and dream-like atmosphere, Salvador Dalí’s masterpiece, The Persistence of Memory, has become a well-known symbol of Surrealism and one of the most famous paintings in the world. Interestingly, the artist was just 28 years old when he completed this masterpiece, but the melting clocks motif he featured in the composition would be a consistent theme in his later works across different mediums.

Surrealists weren’t pleased with him.

Though Dalí is considered a key figure in the Surrealist movement, the group wasn’t happy to have him early in his career. Many in the group were communists and weren’t pleased with Dalí’s fascist sympathies. The artist had a fascination with Hitler that the Surrealists found unsettling. He once said, “I often dreamed about Hitler as other men dreamed about women” and even went as far as to include Hitler in his artwork. This includes 1958’s Metamorphosis of Hitler’s Face into a Moonlit Landscape with Accompaniment, where the Nazi leader’s portrait is disguised in a landscape.

Over twenty years earlier, in 1934, André Breton would call a meeting to try and have Dalí expelled from the Surrealist group, writing “Dalí having been found guilty on several occasions of counterrevolutionary actions involving the glorification of Hitlerian fascism, the undersigned propose that he be excluded from surrealism as a fascist element and combated by all available means.” Of course, Dalí continued with his own beliefs, even supporting Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, whom he met several times.

His signature mustache was inspired by another famous Spanish painter.

Dalí began sporting a chic mustache when he was in his 20s; but as he matured as an artist, his facial hair became more and more prominent. Inspired by Diego Velázquez, a famous artist and portrait painter from the Baroque period, Dalí made his mustache immediately recognizable.

Dalí’s mustache was inspired by Spanish Baroque artist Diego Velázquez.

Diego Velázquez, “Self-Portrait,” c. 1650 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

He had an unconventional marriage.

Elena Ivanovna Diakonova, known as Gala, was ten years older than Dalí and married to Surrealist poet Paul Éluard when she first met him in 1929. A love affair quickly developed, with Gala eventually divorcing Éluard—though they remained close. The couple married in a civil ceremony in 1934, despite Dalí’s family’s unease with him marrying an older Russian divorcee. She had a pivotal role in the artist’s career, becoming his business manager and muse.

By the 1950s, Gala was publicly engaged in extramarital affairs, though it’s said that Dalí encouraged this. And in 1969, when Dalí purchased her a Catalan castle in Púbol, it was specified that he could visit her there only if invited in writing. Throughout their lives, there’s no doubt they shared an intense and cerebral love. He wrote, “I would polish Gala to make her shine, make her the happiest possible, caring for her more than myself, because without her, it would all end.”

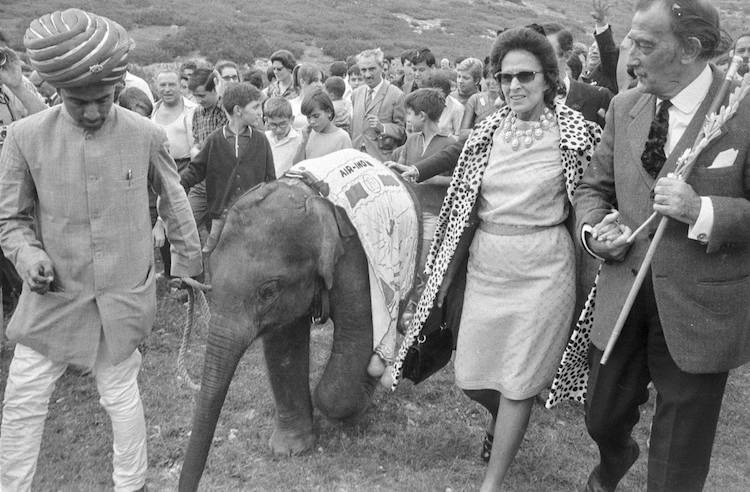

Photograph of Dalí and Gala receiving an elephant, which was a gift from Air Bus airlines, 1967 (Photo: Ajuntament de Girona)

He tricked Yoko Ono.

Always up for a prank, some consider Dalí a bit of a con man. Close friend and muse Amanda Lear recalls how he once duped Yoko Ono, selling her a blade of grass for $10,000. Apparently, Ono had asked Dalí to sell him a strand of hair from his infamous mustache. Not one to turn down a check, he got creative.

“Dali thought that Yoko Ono was a witch and might use it in a spell. He didn’t want to send her a personal item, much less one of his hairs,” Lear explained. “So he sent me to the garden to find a dry blade of grass, and sent it off in a nice presentation box. The idiot paid 10,000 dollars for it. It amused him to rip people off.”

He collaborated with Disney.

In 1946, Salvador Dalí and Disney designer John Hench worked on an animated film together called Destino. Dalí created 22 oil paintings and countless drawings that Hench then turned into film storyboards. However, just 8 months in, the work stopped due to financial reasons and the film was left unfinished, with only 15 seconds of demo reel completed.

In 1999, Walt Disney’s nephew and longtime senior executive for The Walt Disney Company, Roy E. Disney, decided to revive the production of Destino. The finished, 6-minute short was released in 2003 and tells the story of a ballerina on a surreal journey through a desert landscape.

He designed the Chupa Chups logo.

Dalí had no issue participating in commercial work. He designed ads for Gap and even appeared in a commercial for Lanvin chocolates in 1968. In fact, André Breton, the father of Surrealism, gave him the nickname “Avida Dollars” or “eager for dollars.” But one of his most enduring contributions to graphic design is the Chupa Chups logo. Dalí designed the logo for the Spanish lollipop brand in 1969, and it is still used today.

He loved throwing dinner parties.

Dalí and his wife Gala loved staging elaborate dinner parties. But, in true Dalí fashion, these weren’t ordinary dinners. Guests were asked to arrive dressed in costume to match the evening’s theme and wild animals would roam free around the room. In 1973, he even published a cookbook—Les Diners de Gala—with recipes for bizarre items like “Veal Cutlets Stuffed with Snails” and “Toffee with Pinecones.”

He paid his restaurant bills in doodles.

Thrifty and clever, Dalí found an innovative way to get out of paying for a meal. It’s said that when he dined with a large group of friends, he would offer to pay the bill. He’d then pay with a check, but include a doodle on the back knowing that the check would never get cashed seeing as the doodle he’d left was infinitely more valuable.

He moonlighted as a fashion designer.

Dalí loved fashion. He worked closely with Italian designer Elsa Schiaparelli, who created designs based on his artwork. In particular, his Aphrodisiac Lobster Telephone was an inspiration, and they worked on a lobster dress for Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor, in the 1930s. He also created a shoe-shaped hat, a belt with lips as a buckle, perfume bottles, and numerous textile designs. In 1950, he collaborated with close friend Christian Dior on a project about fashion inspired by the future. Dalí’s contribution was “A dress for 2045.”

He produced covers for Vogue.

When we think of Vogue covers, photographs of supermodels come to mind. But Dalí created four covers for the legendary fashion magazine. His first, the December 1938 cover, shows two women. The woman in the foreground has a head formed from flowers, while the woman in the background has branches streaming from her head. His April 1944 design sees him incorporate the word Vogue into his art piece. For the December 1971 issue, he not only designed the cover, but also acted as editor.

He designed jewelry—including a pulsating heart.

The Royal Heart is a dazzling masterpiece crafted from 18k gold and covered with 46 rubies, 42 diamonds, two emeralds, and other precious gems. And that’s not the most impressive part. An internal mechanism causes The Royal Heart to beat as though it were a live human heart.

The Royal Heart is the centerpiece of the Dalí-Joies collection now located at the Dalí Museum in Figueres, Spain. The collection started in 1941, when American millionaire Cummins Catherwood acquired 22 pieces by the artist. He’d designed the jewels on paper and closely supervised Argentinian goldsmith Carlos Alemany, who executed the work. Dalí continued to add to the collection, which passed through the hands of many, including a Saudi millionaire and several Japanese collectors. In 1999, the Salvador Dalí Foundation purchased all 41 jewels, as well as Dalí drawings and paintings of the designs, for €5.5 million (nearly $7 million).

He created a hologram of Alice Cooper.

Though they may seem like an unlikely pairing, Salvador Dalí and musician Alice Cooper had a mutual admiration for one another. Cooper, who was an art student in high school, modeled his early stage shows after the Surrealist painter. When Dalí discovered this, he was impressed. “Dalí’s people rang my manager and explained that he’d seen one of my stadium shows,” Cooper told Another Man. “He said it was like seeing one of his paintings come to life, and that he wanted us to work together.”

Cooper was just 25 years old when he and Dalí met in 1973. The 69-year-old painter arrived with an elaborate entourage and suggested that he create the world’s first living hologram—using Cooper as the model. He not only created First Cylindric Chromo-Hologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain, but also presented the singer with a sculpture titled The Alice Brain. The ceramic sculpture of a brain had a chocolate eclair running down it and ants that spelled the words “Alice” and “Dalí”.

“I said: ‘That’s great, when we’re done can I have it?’ ” recalls Cooper. “He said ‘Of course not, it’s worth millions!’ I just laughed. He had a great sense of humor but his genius was that you never knew when he was being funny and when he wasn’t.” Cooper and Dalí’s encounter remains one of the great artist/musician collaborations in history.

He illustrated a copy of Alice in Wonderland.

There’s no better surreal imagery for Dalí than the equally bizarre tale of Alice in Wonderland. In 1969, Random House asked the artist to illustrate a limited edition of the Lewis Carroll classic and the results are as good are you’d think. Only 2,700 copies were created, but luckily a new reissue ensures that the work will live on. Dalí created 13 designs for the book, one for each chapter and the cover. The work is filled with signature Dalí touches—the iconic melting clock from The Persistence of Memory finds a nice home at the center of the Mad Hatter’s tea party.

Photo: Stock Photos from imagIN.gr photography/Shutterstock

He built his own museum.

Dalí not only created his own museum, he’s also buried there. Located in his hometown of Figueres, the project started in the 1960s when the mayor of the small Catalan town asked Dalí to donate a piece of art to the city museum. Dalí decided to do much more than that, transforming the town’s theater—which was nearly destroyed during the Spanish Civil War—into the Dalí Theater and Museum.

The museum officially opened in 1974, but Dalí continued to expand the museum and even lived there during the final years of his life. After his death in 1989, he was buried under the stage of the theater. Today, the museum draws more than 1 million visitors a year, who flock to see the largest collection of Dalí’s artwork.

His trademark mustache remains intact to this day.

In July 2017, Dalí’s body was exhumed as part of a paternity suit brought on by a woman named María Pilar Abel Martínez who claimed to be his daughter. The exhumation proved her wrong, but it did reveal one surreal discovery: The Spanish artist’s mustache still remains perfectly groomed. “I was eager to see him and I was absolutely stunned. It was like a miracle, said Narcis Bardalet, who was in charge of embalming Dalí’s body. “His mustache appeared at 10 past 10 exactly and his hair was intact.”

This article has been edited and updated.

Related Articles:

Quirky Salvador Dalí Doll Includes Interchangeable Mustaches and a Melting Clock

Photographer Recreates Philippe Halsman’s Iconic 1948 “Dalí Atomicus” Image

What is Modern Art? Exploring the Movements That Define the Groundbreaking Genre

20 Revolutionary Art Movements That Have Shaped Our Visual History